Q & A with Stephen Palmer of Artists' Newletter

Questions for Alan Currall

1. How did the idea for ‘Encyclopaedia’ come about?

I’d been working with ideas around the human need to find faith in some things in life, no matter how implausible, and our willingness to suspend disbelief. This usually resulted in self-shot performance to video-camera monologue type works. In 1996 I made a three channel video work called ‘Survival kits: Shipwreck, plane crash and nuclear war’, in which I asked my parents for advice on surviving each of these impossible scenarios. They were totally up to the challenge and took it all in their stride; offering such valuable tips as drinking seagull blood for sustenance, sitting at the back of the plane to improve one’s chances and preparing for a nuclear holocaust with bin-bags and sunglasses.

I really appreciated the ability my non-artist parents had to speak truth to the absurdity of a given situation in such an unaffected way that I struggled to produce myself, with all my self-conscious knowingness. Following this, in 1999, I made a piece called ‘Self Defence / First Aid’ and again I called upon the participation of family; asking my sister and brother for advice on dealing with an extreme situation. By this time I was beginning to be interested in the possibilities of making work for an online context. So instead of shooting this to video I recorded, as audio, the advice as given to me over the telephone.

‘Encyclopædia’ was a natural progression from this strand of my practice. I’d been working with all this apocryphal knowledge and advice and started to think about the total sum of my knowledge base and world view; how much of this was formed through pub-table conversations and the casual but confident proclamations of the people I’d grown up with.

My initial desire was that this idea could somehow work as an online piece, creating a universally accessible fount of all knowledge (albeit of unauthorised provenance). However, this was years before Youtube and still in an age of dial-up 33.6 kbps modems. Putting streaming video online was not an option. The closest analogy for this kind of democratisation of knowledge in a digital form, at the time, can be seen in the various encyclopædias that started being produced on CD-ROM. These began, to my knowledge, with the digital version of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which was originally very expensive to purchase (although not as much as the printed edition). Not long after, other publishers started producing versions of their own, bundling them with PC sales and then ultimately giving them away free with newspapers. So much so that the format became both ubiquitous and somewhat devalued during the 1990s.

2. What equipment did you use to produce 'Encyclopaedia'?

I used a Panasonic NV-DX100 miniDV video camera, an Audio Technica 835b short shotgun microphone, a Umax Macintosh clone (can’t remember the model number), an external Lacie CD-ROM burner, Adobe Premiere 4.2, Adobe Photoshop 3 and Macromedia Director 5. All of this equipment, which amounted to a small personal fortune for me, was bought using money I received upon winning the 1998 Richard Hough Bursary (at the time, Scotland’s biggest artists’ prize).

3. How do you think our attitude to information and knowledge has changed since you made the work? Do you think the fact that real people are speaking to us in ‘Encyclopaedia’ gives the work a sense of validity that might be missing from online encyclopaedias such as Wikipedia?

I don’t know if it makes the work any more valid. I’m sure Wikipedia is authored by real people too. I think it’s important that these are all people I have had close personal relationships with at various times in my life. This meant that, however self-conscious or uncomfortable they might appear in front of the camera, there is very little attempt by anyone to represent themselves as anything other than the person I know (or at least think I know) them to be.

Maybe the fallibility of the contributors to ‘Encyclopædia’ is made a little more obvious by the lack of any attempt to polish up and smooth off the production values of the videos. I think maybe this fallibility attests to the vulnerability of all apparently ‘certain’ knowledge.

I think the World Wide Web has certainly changed most people’s attitude towards information and knowledge. The supposed checks and balances that existed in published information before the advent of the WWW created a smokescreen of validity, carefully calibrated by the economic muscle of each publisher. Although there is still a vestige of this evident in the main portals and search engines that are increasingly steering our internet usage, I think the curtain was lifted long enough for us to see just how fragile any claim to an absolutely authorised version of the truth might be. And of course the whole recent and ongoing Wikileaks and related exposure of the harvesting and control of information stories, only go to increase our skepticism.

4. How do you think the work stands up in this remastered form and in the context of today’s culture of social media abundance?

Matthew Jarvis has done an incredible job of porting the whole work to an online platform and I can’t praise him enough for this. It’s still interesting to see the two versions side by side and make comparisons though. As far as we might have come with online media authoring, there are still some compromises that have to be made in the name of bandwidth and browser compatibility. The graphic and interactive design of ‘Encyclopædia’ were pretty modest, even for its day. This was a deliberate decision, having seen a lot of CD-ROM work around this time. It was, for a brief flash in the pan, what we would now call a trending format. As with all new media, a lot of people were really pushing the envelope of what was possible and creating some pretty sophisticated interactive screen-based work. I knew that this approach had little to offer me in my interest in using the format.

As regards our ‘culture of social media abundance’, firstly I guess it’s important to remember that this is a period piece. There are whole new channels of interconnectedness that we have access to now in creating relationships and sharing information. To attempt to make this work, as it stands, today would be anachronistic. Perhaps more importantly though, is the point I made earlier about the closeness of the relationships that I had with the contributors. These ranged from contemporary friends and family to old friends I hadn’t seen for years. I traveled the length and breadth of the country to catch up with people I’d had to track down again having long since lost contact with. There are some people you find in life that if you meet up with them again years later you are still able to just click into synch with. This had a direct bearing on the manner and the quality of the contributions these people were willing and able to give to ‘Encyclopædia’. These aren’t the kinds of relationships one makes on Facebook or Youtube.

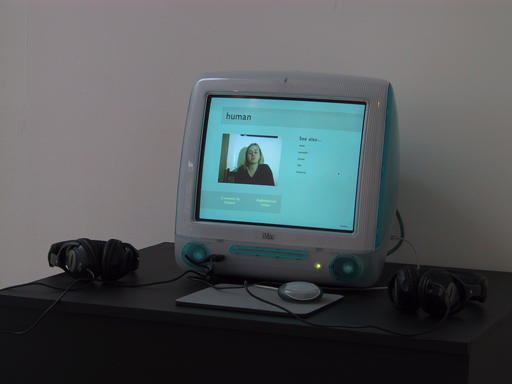

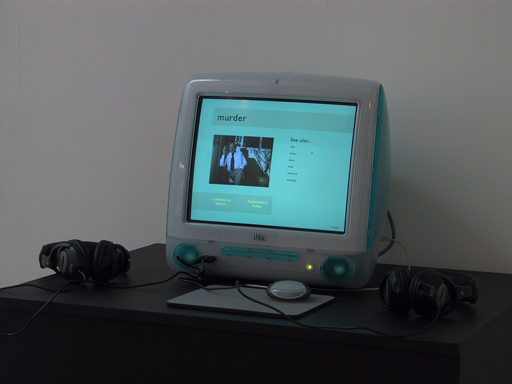

Encyclopædia, 2000

CD-ROM. Redux online edition, 2013

Commissioned and published by Film and Video Umbrella. Originally part of a Film and Video Umbrella Touring Exhibition. Curated and produced by Film and Video Umbrella, Stills and Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.

Supported by the National Touring Programme of the Arts Council of England.

This work was first shown, in 2000, as a centrepiece to the exhibition, Encyclopædia and Other Works at The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, England. This show travelled later in the same year to Stills Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland and, in 2001, to Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, Australia.

Encyclopædia has since featured in several exhibitions including:

- Database Imaginary, Walter Philips Gallery, Banff, Canada. Saidye Bronfman Center for the Arts, Quebec, Canada. Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, 2004.

- Alan Currall, The Jerwood Gallery, London, England, 2002.

- Encyclopædia, Image Gallery, Bedford, England. Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, England. Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, Australia, 2001 and Aspex Gallery, Portsmouth, England. Angel Row Gallery, Nottingham, England, 2000.

- Alan Currall, Signal Gallery, Malmo, Sweden, 2000.

- Click, Bendigo Art Gallery, Geelong Art Gallery, Latrobe Regional Gallery, Mildura Arts Centre Gallery and Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery, Victoria, Australia.

Encyclopædia, in its original CD-ROM, a format is no longer compatible with current computers. plus a link to the online version can be found on the Film and Video Umbrella website, here. As part of Film and Video Umbrella's 25 Frames programme, the work was faithfully replicated, in 2013, to resemble the original as closely as possible and to be viewed on a wide range of web browsers and tablet computers. This online version can be found here.

Further information about this work, including a newly commissioned text by the author Henry Hitchings can be found here.

A recording of Alan Currall in conversation with Mike Jones, of Film and Video Umbrella, on Encyclopædia can be found here.