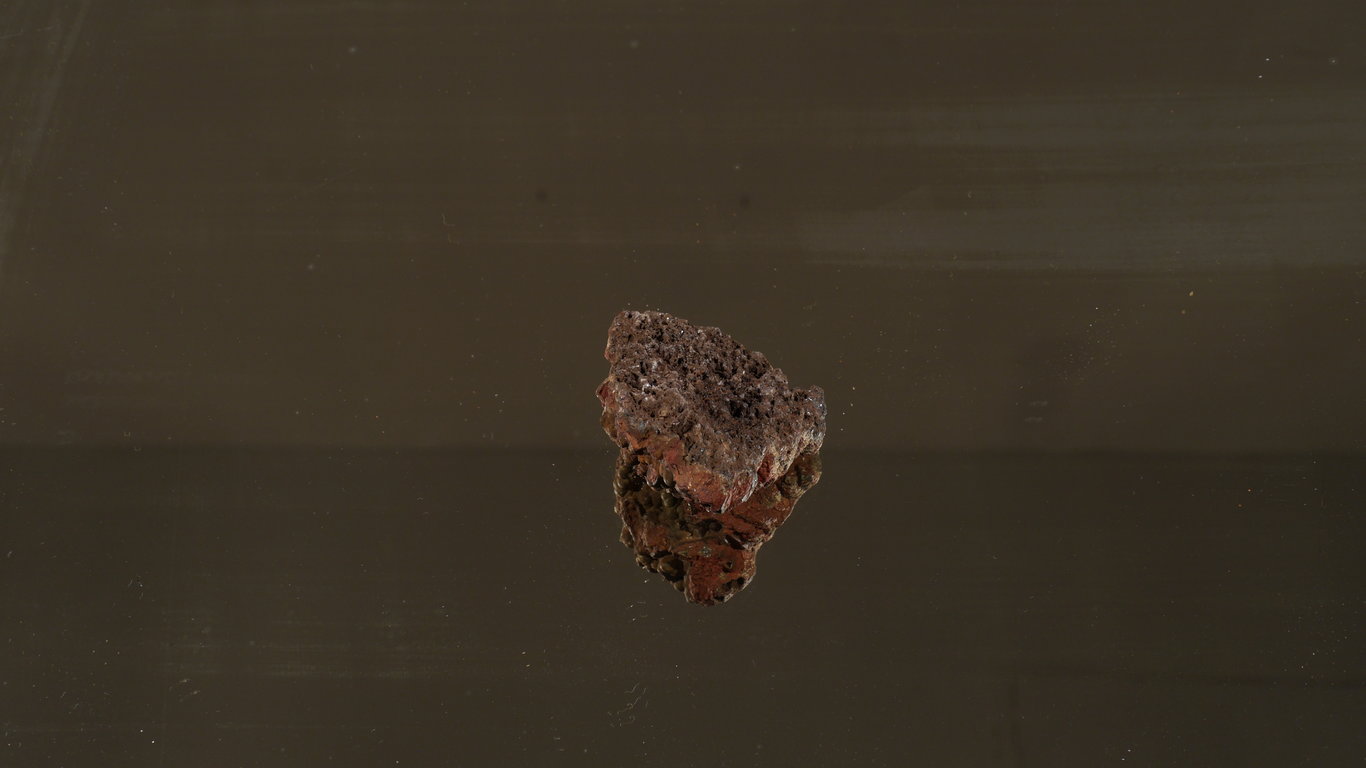

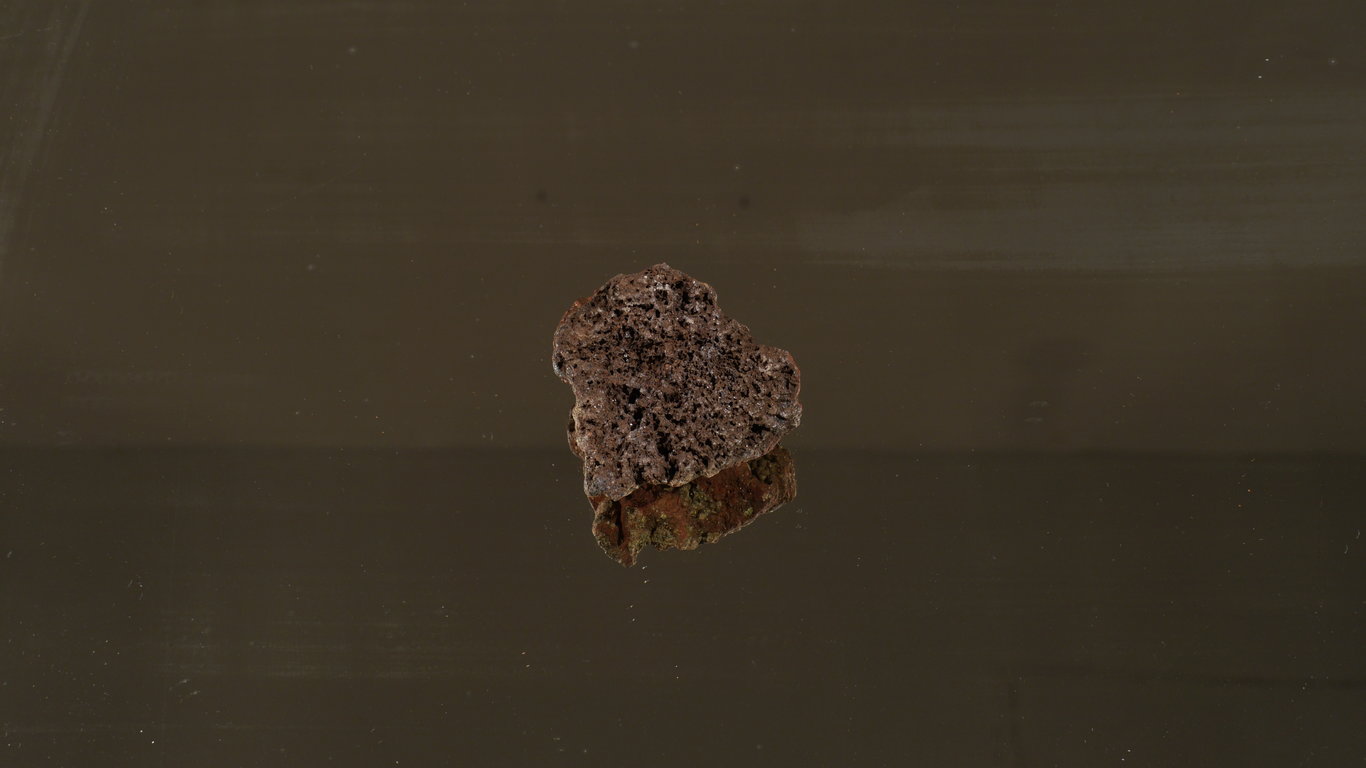

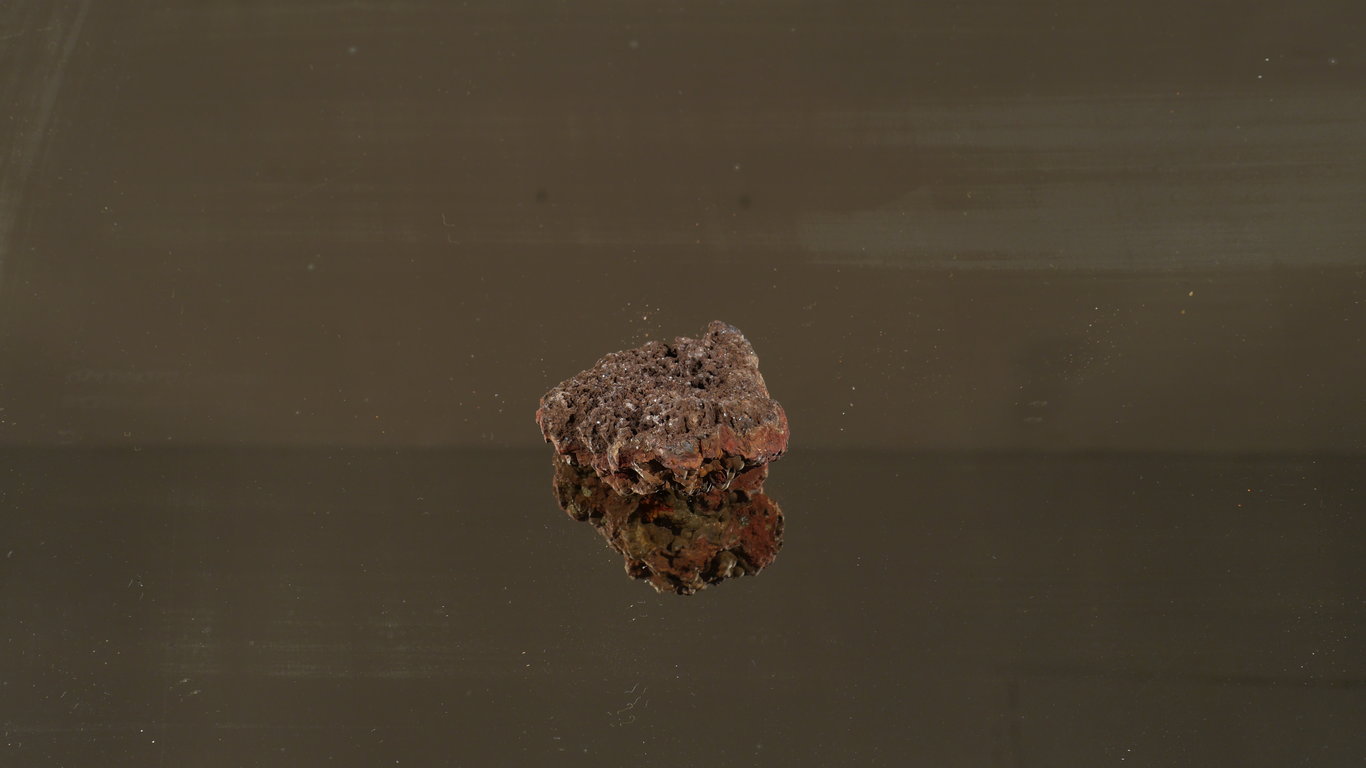

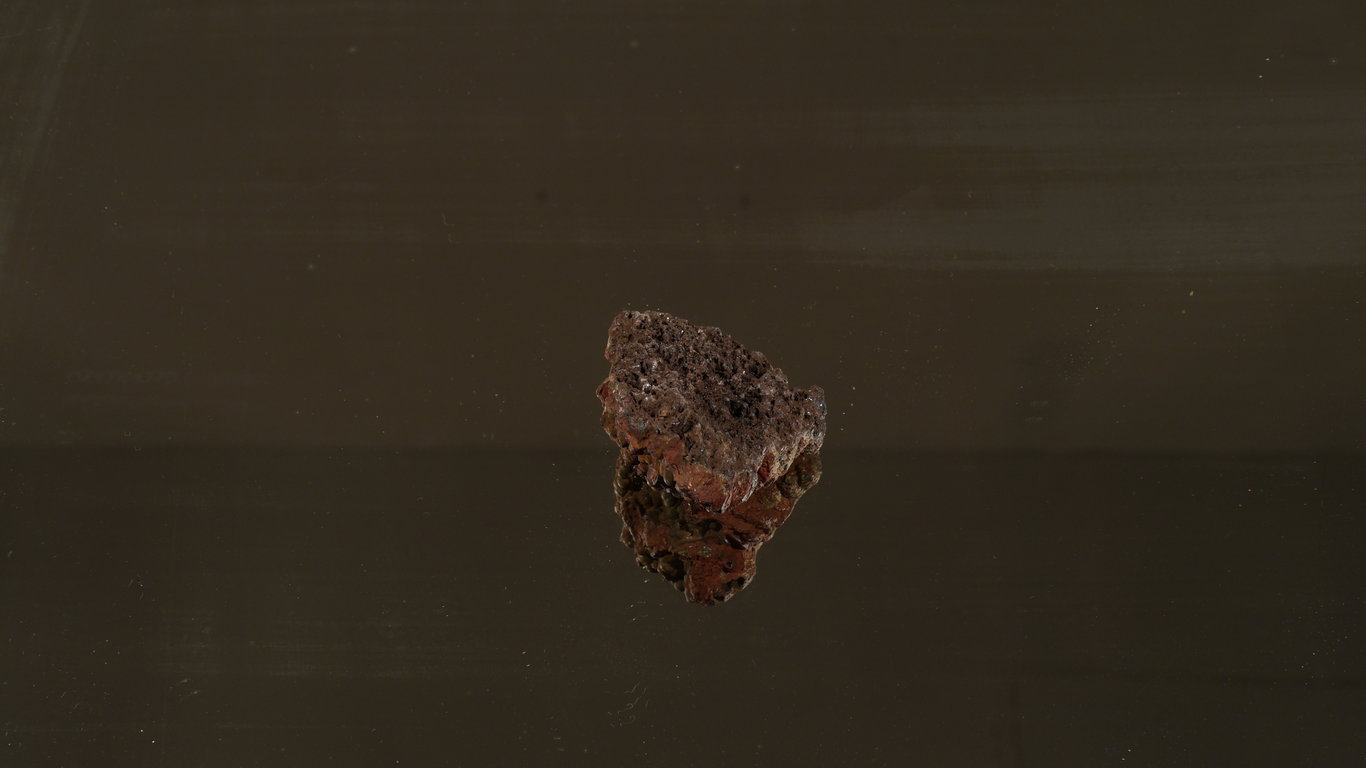

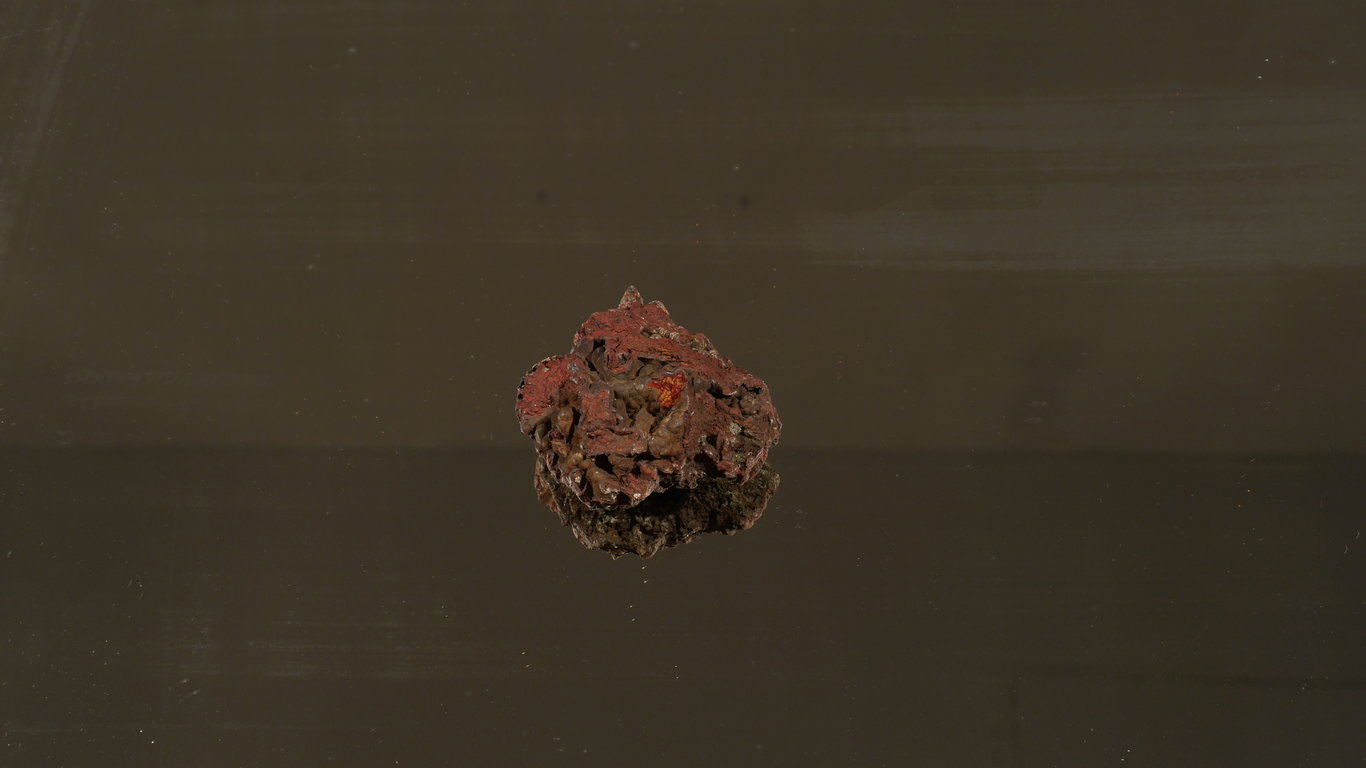

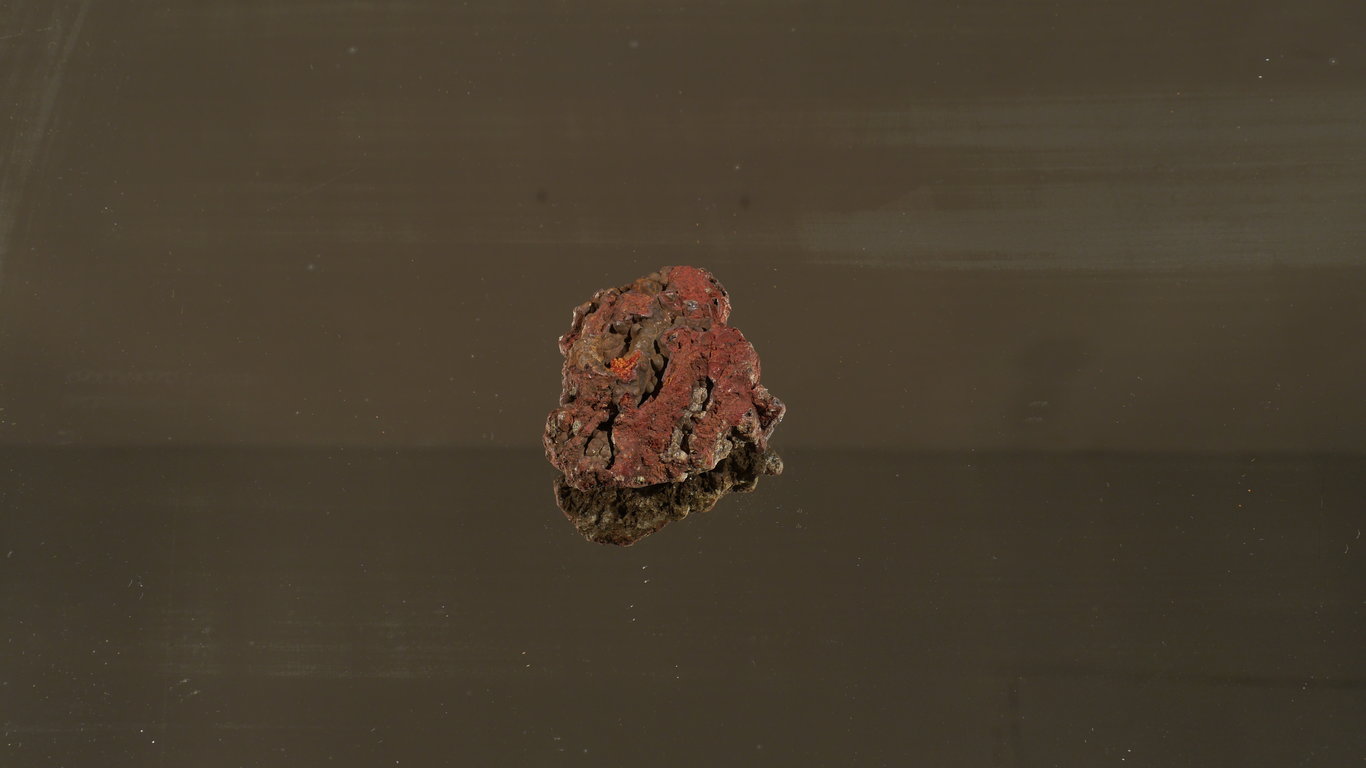

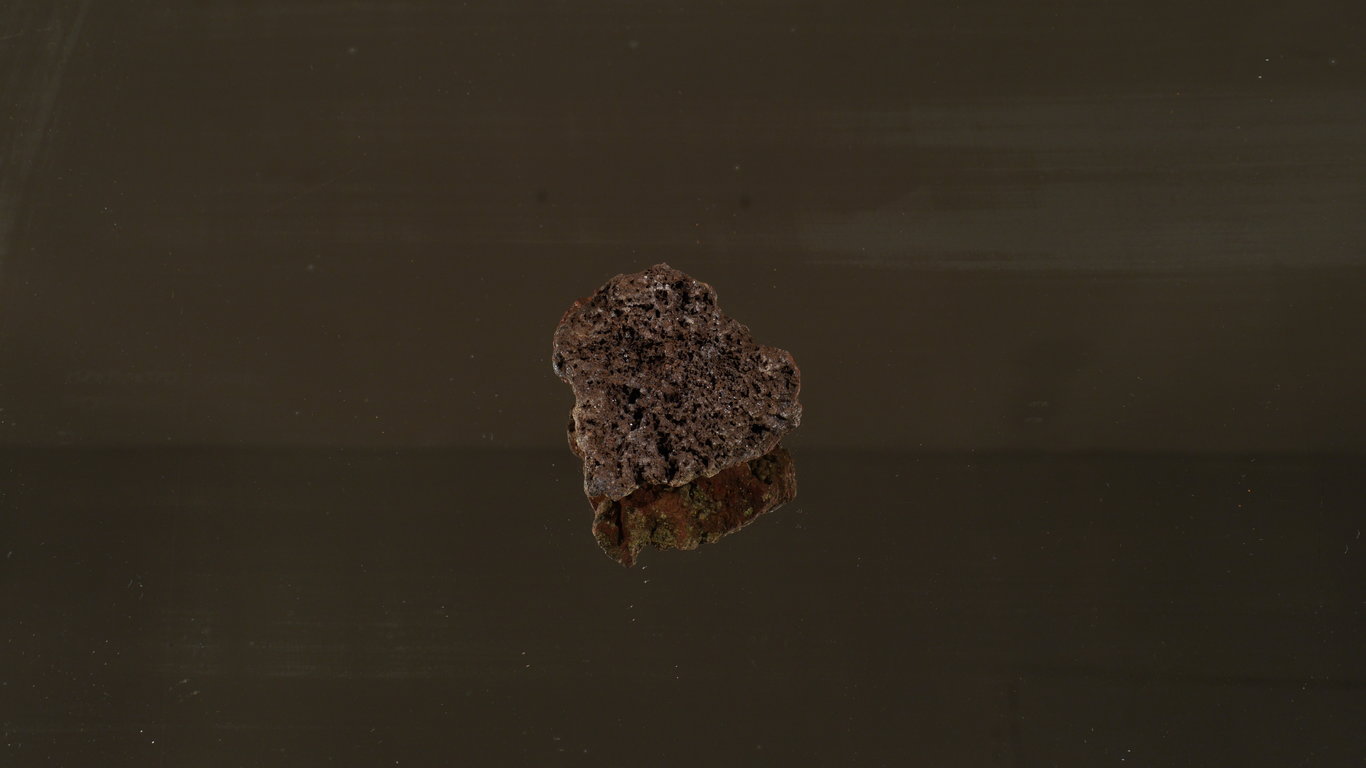

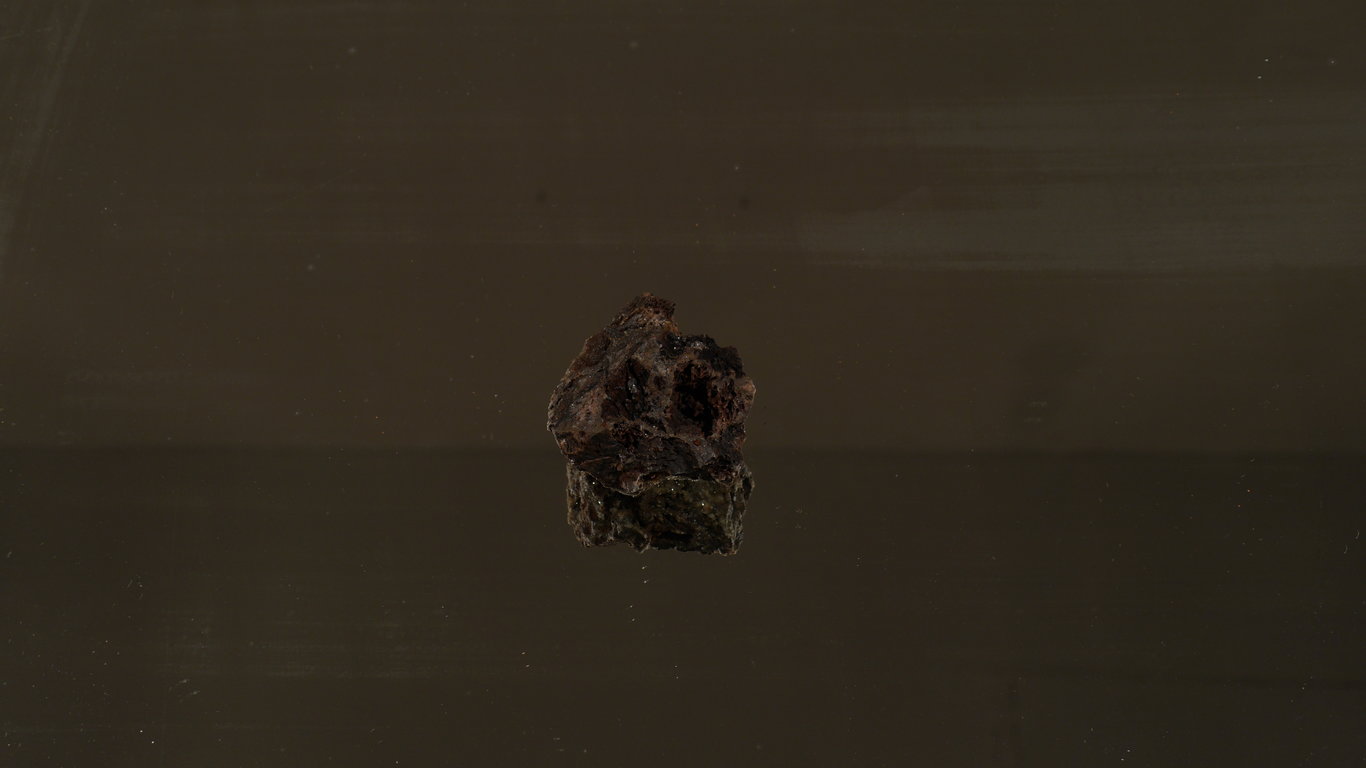

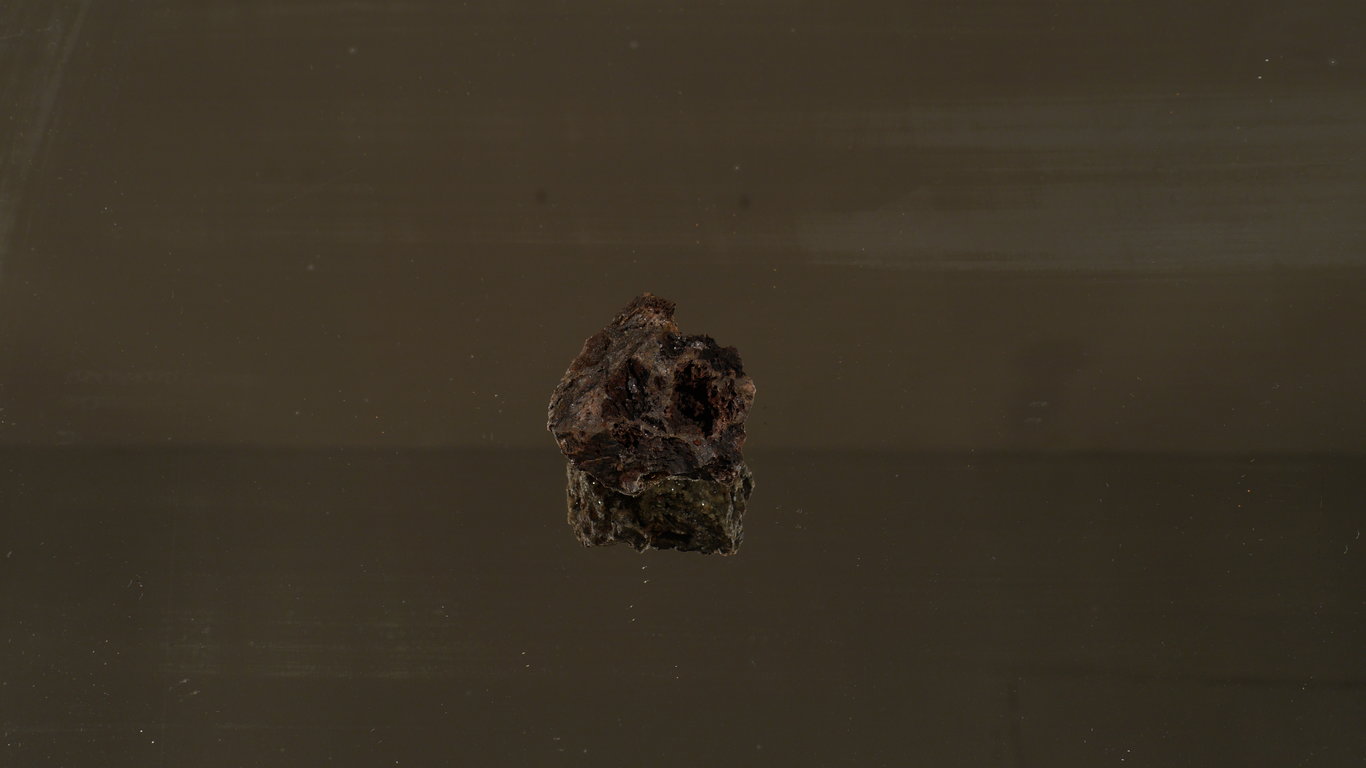

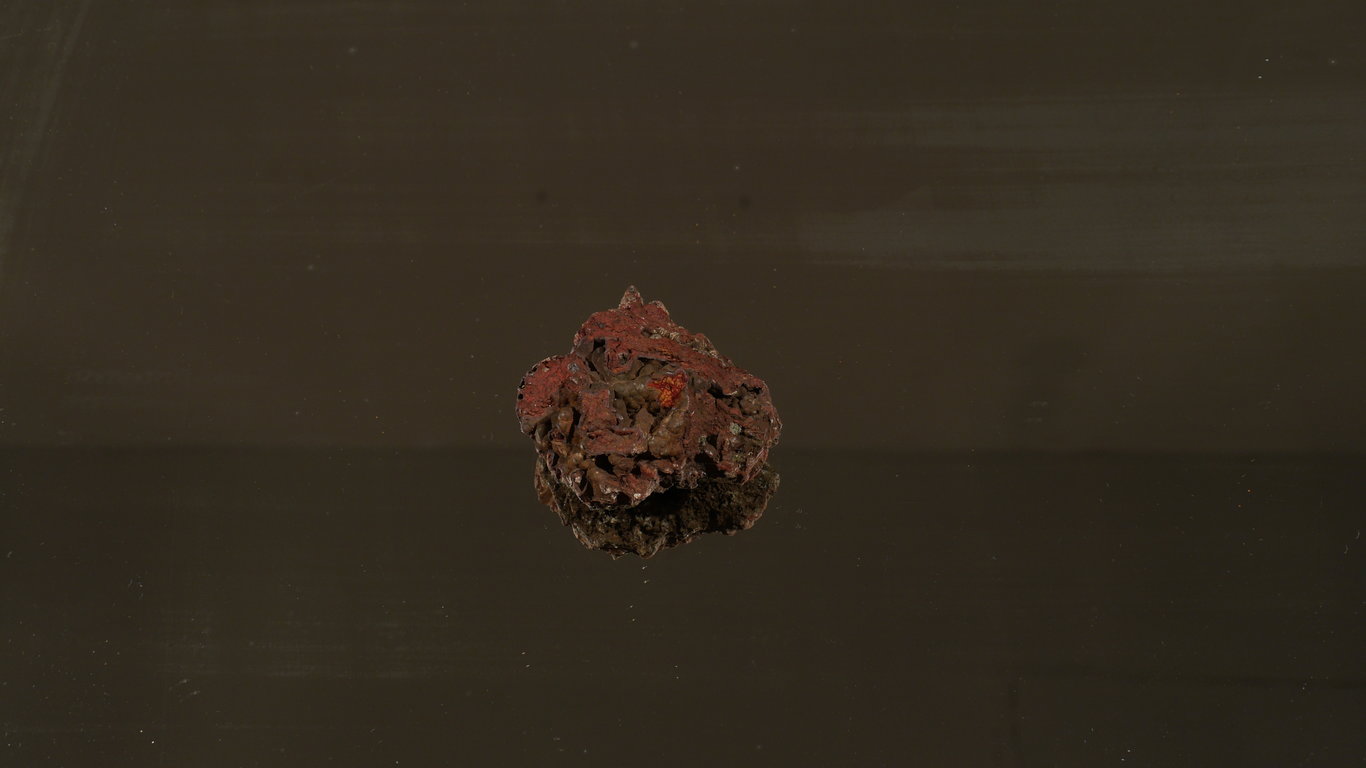

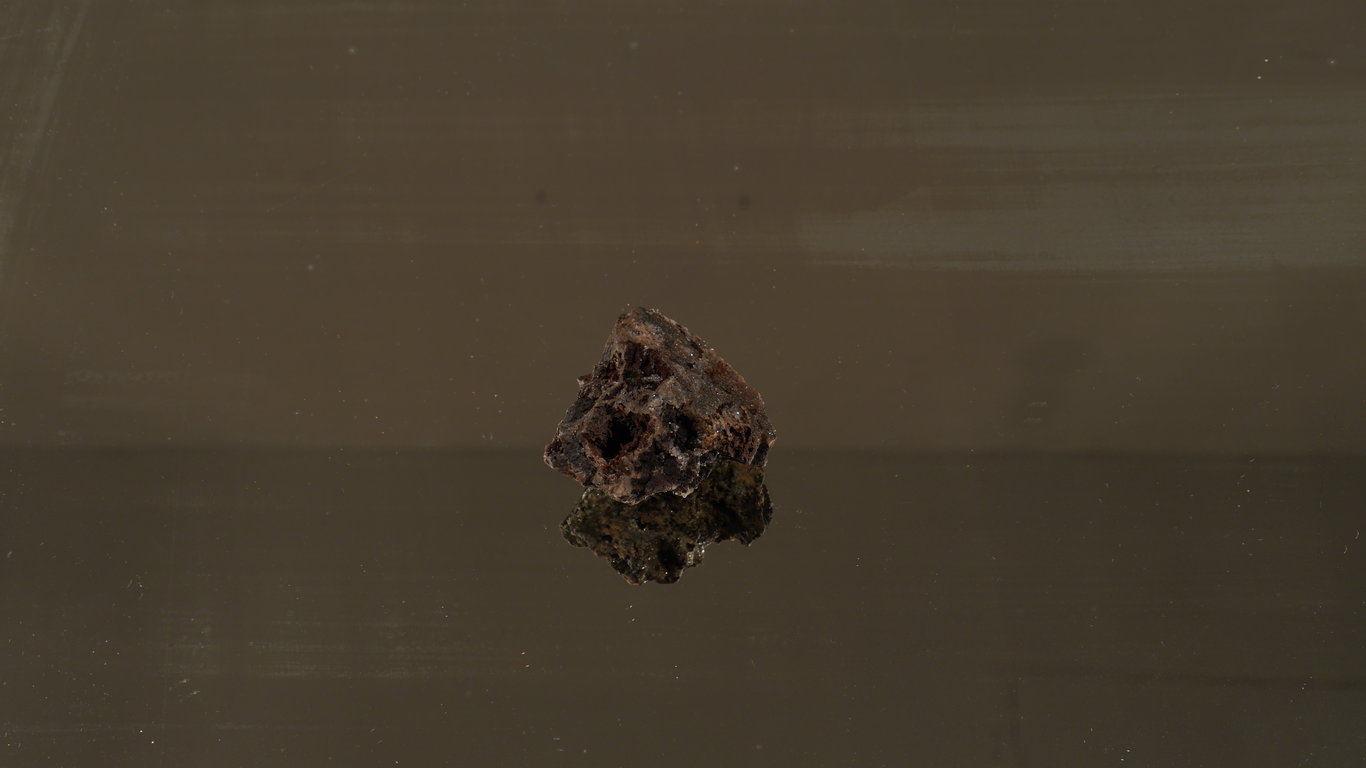

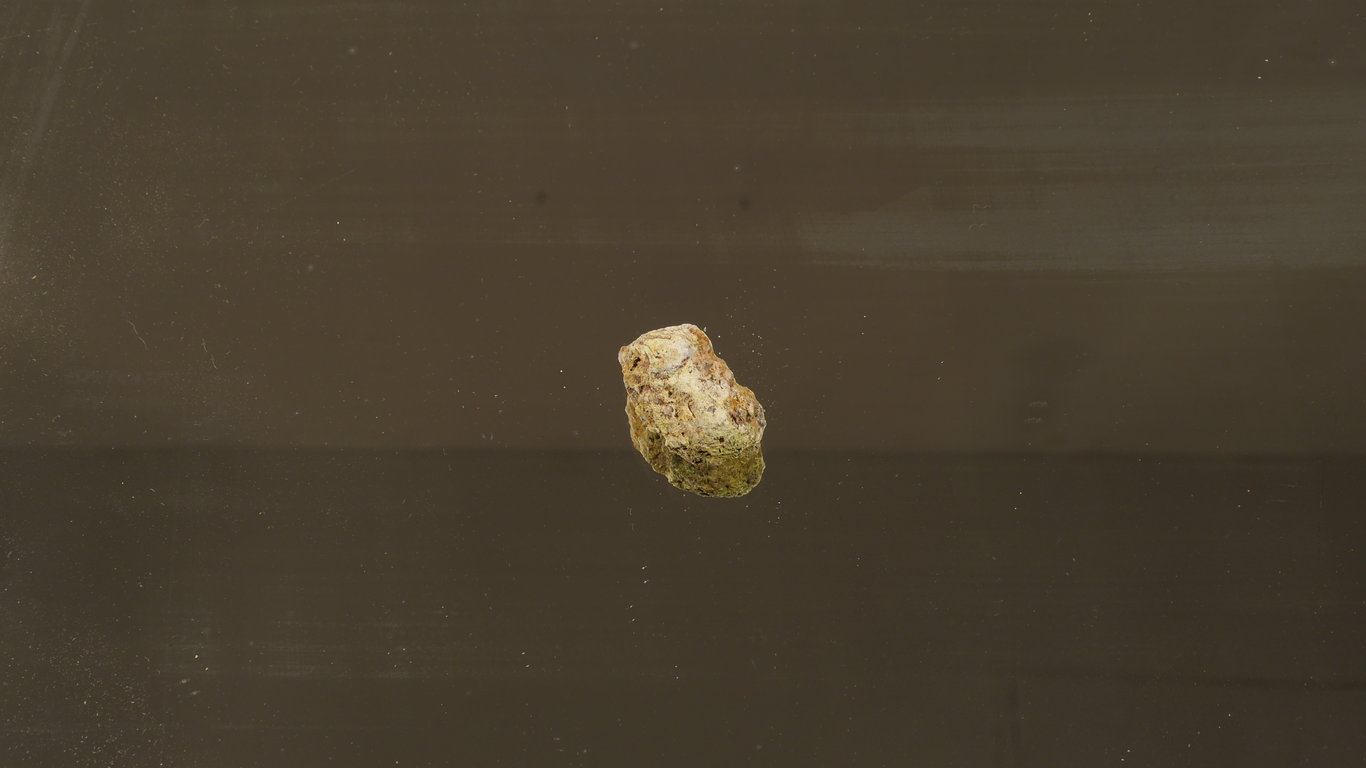

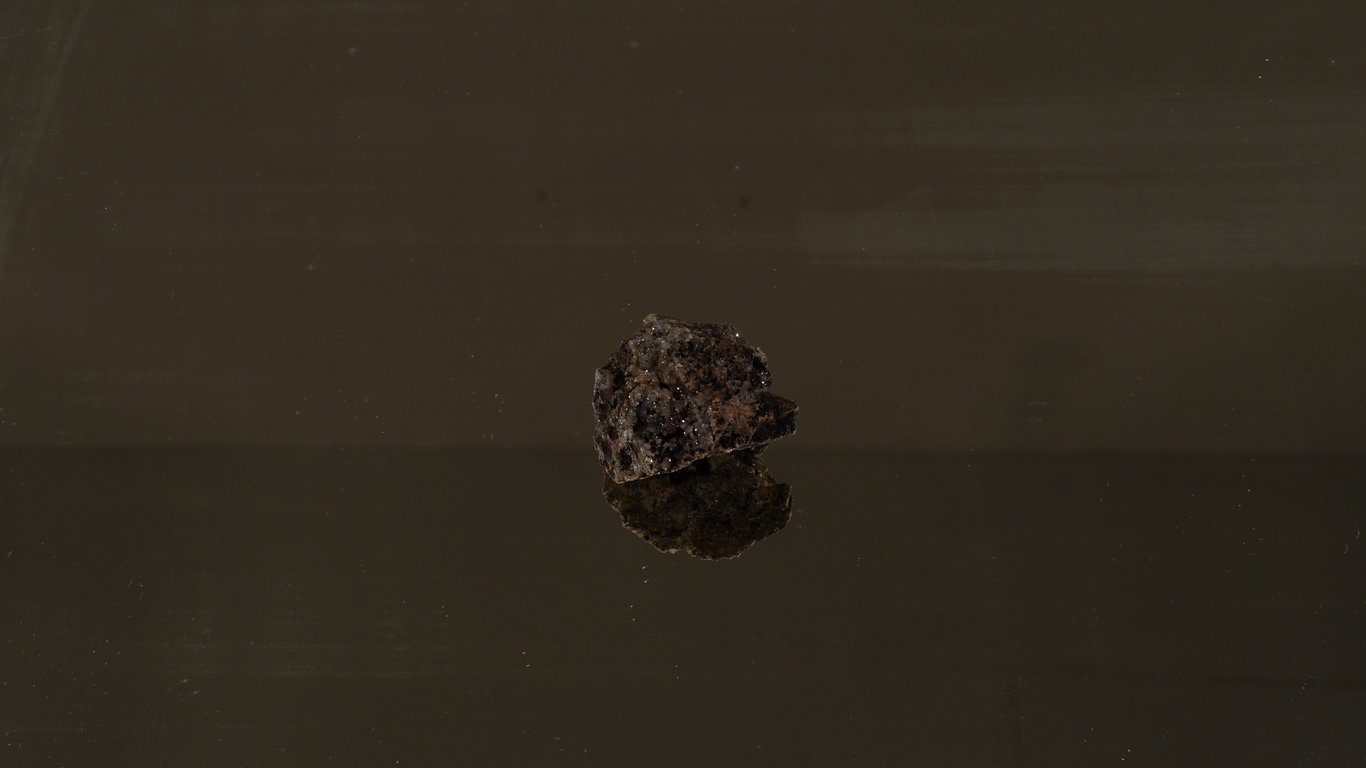

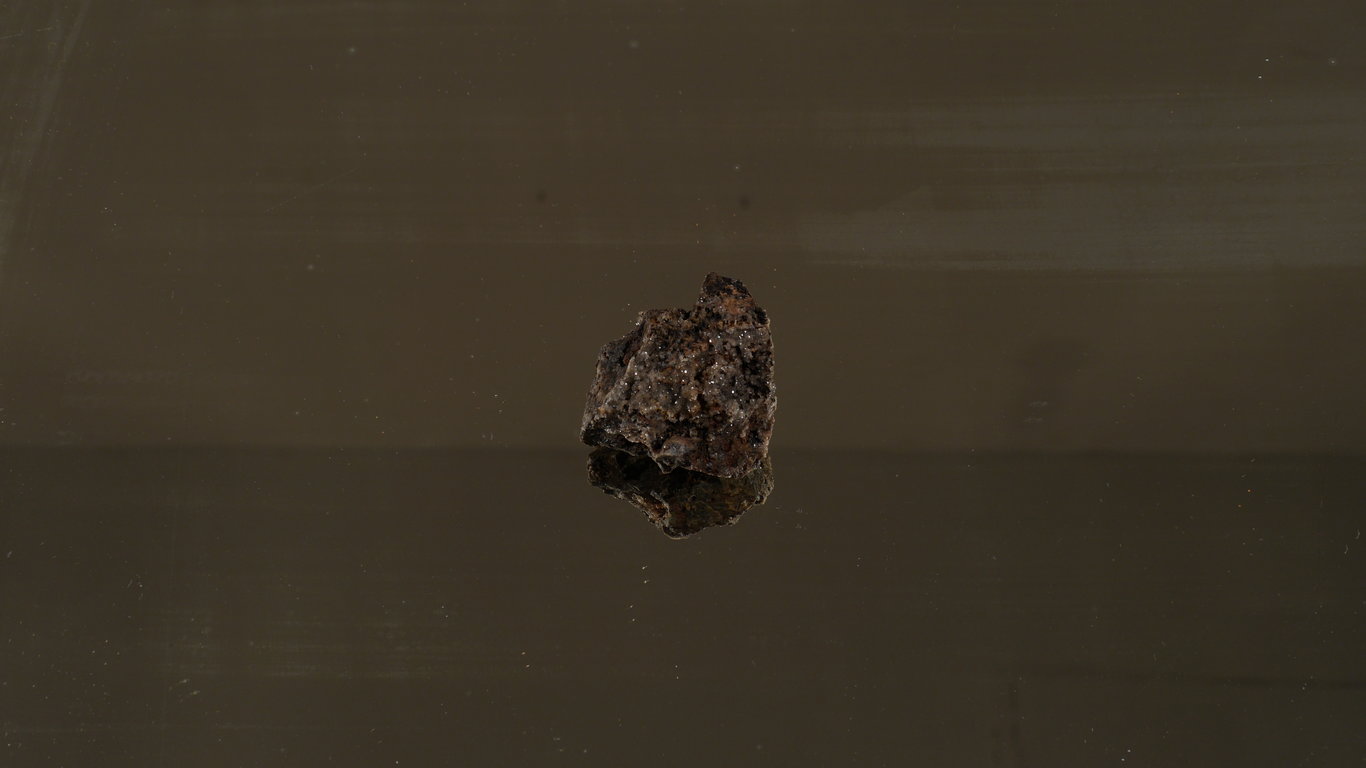

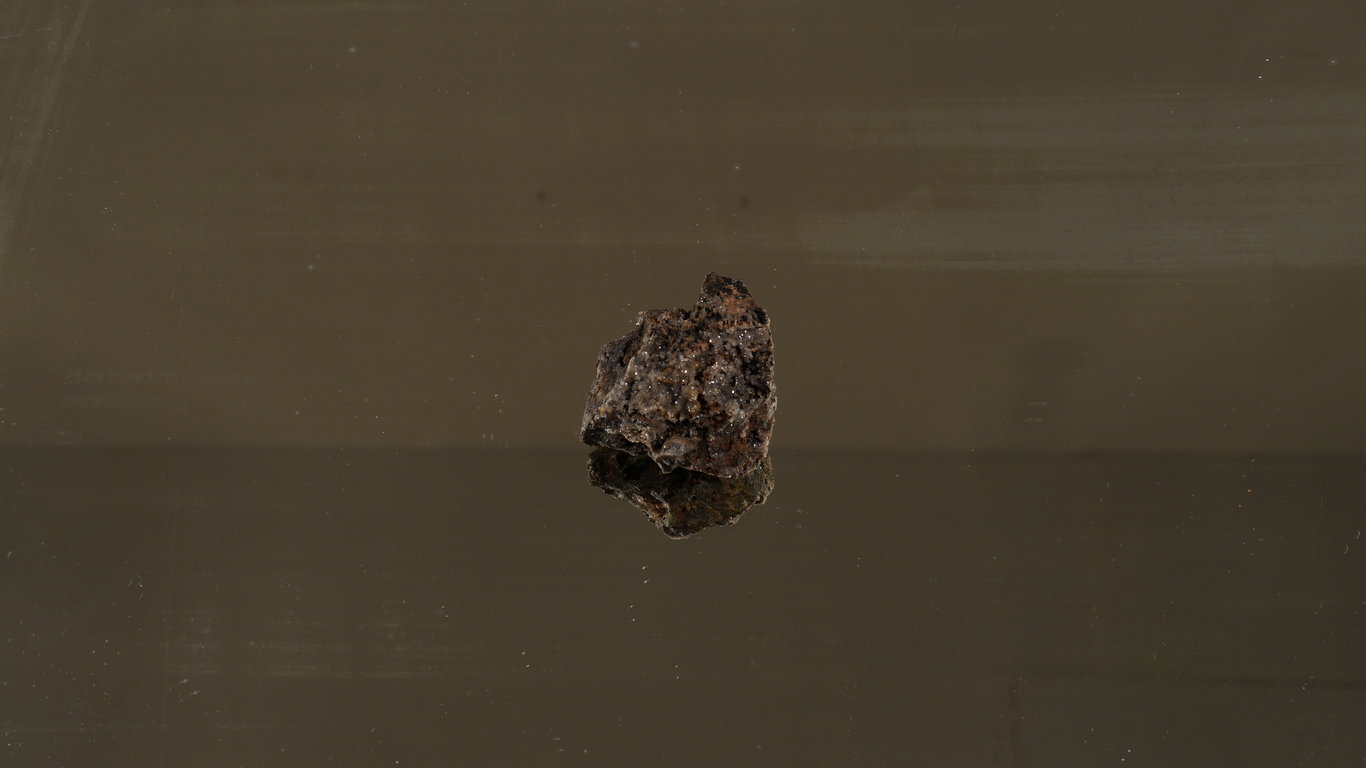

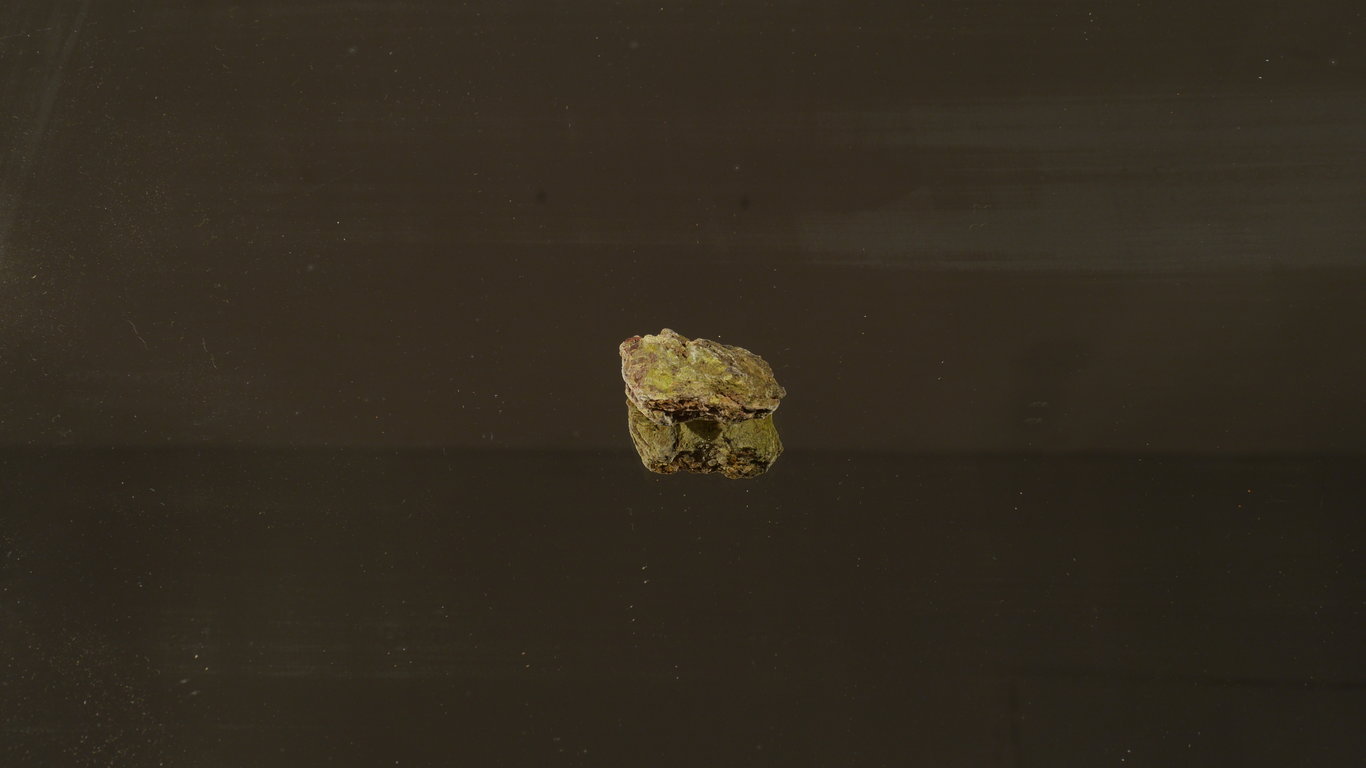

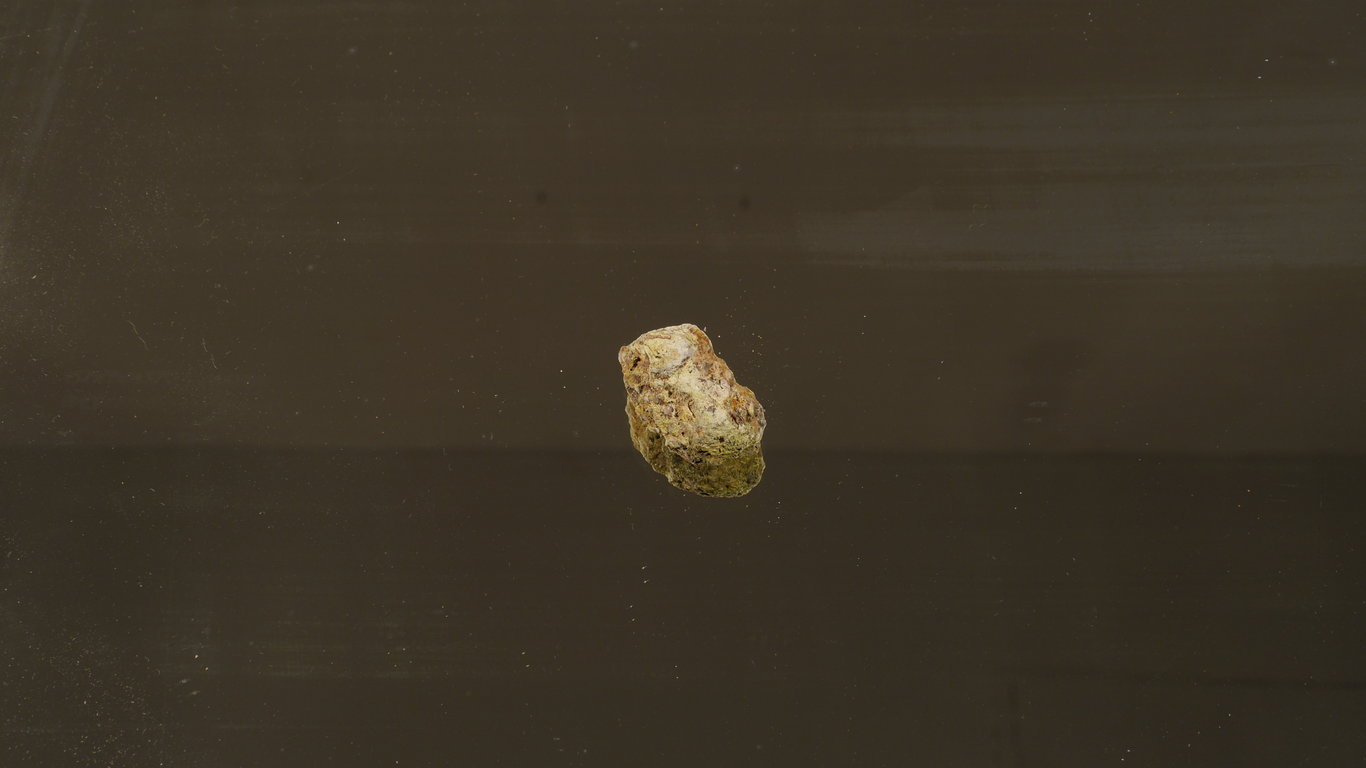

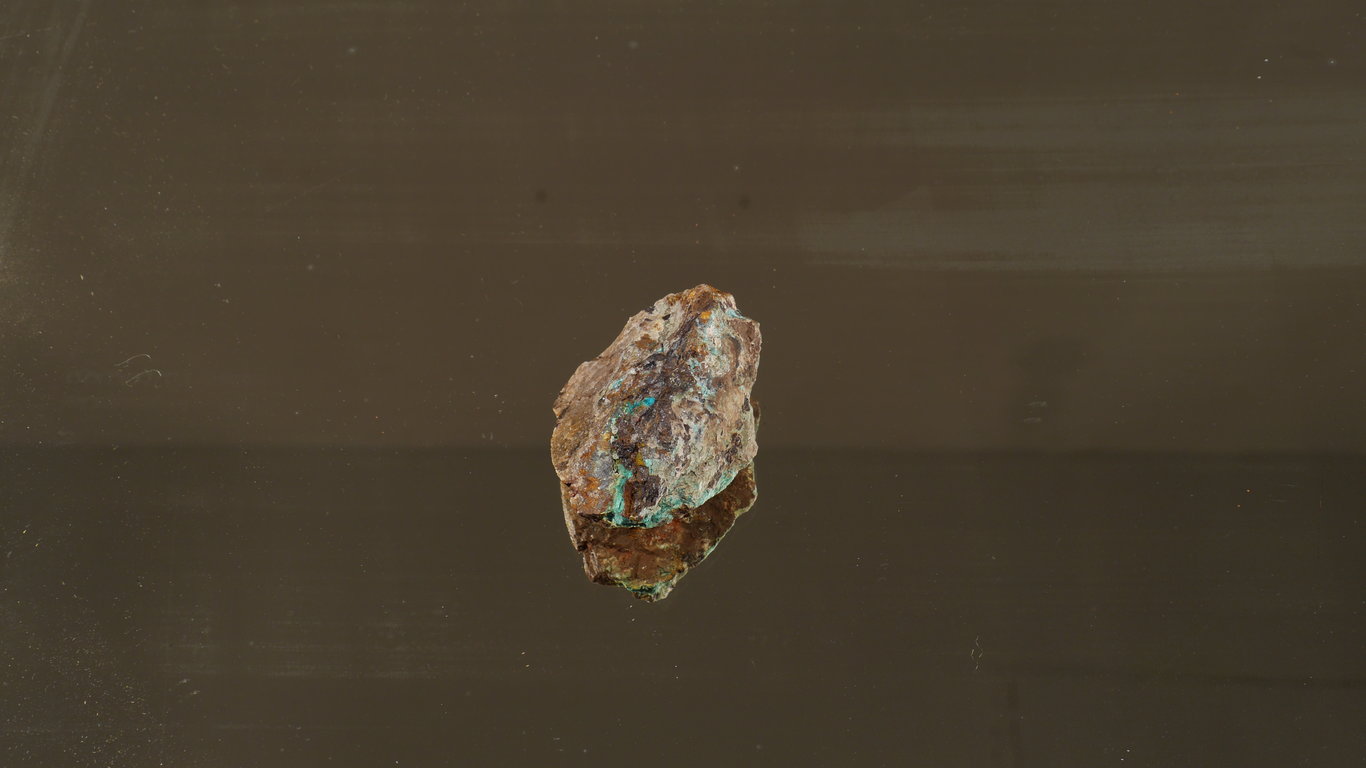

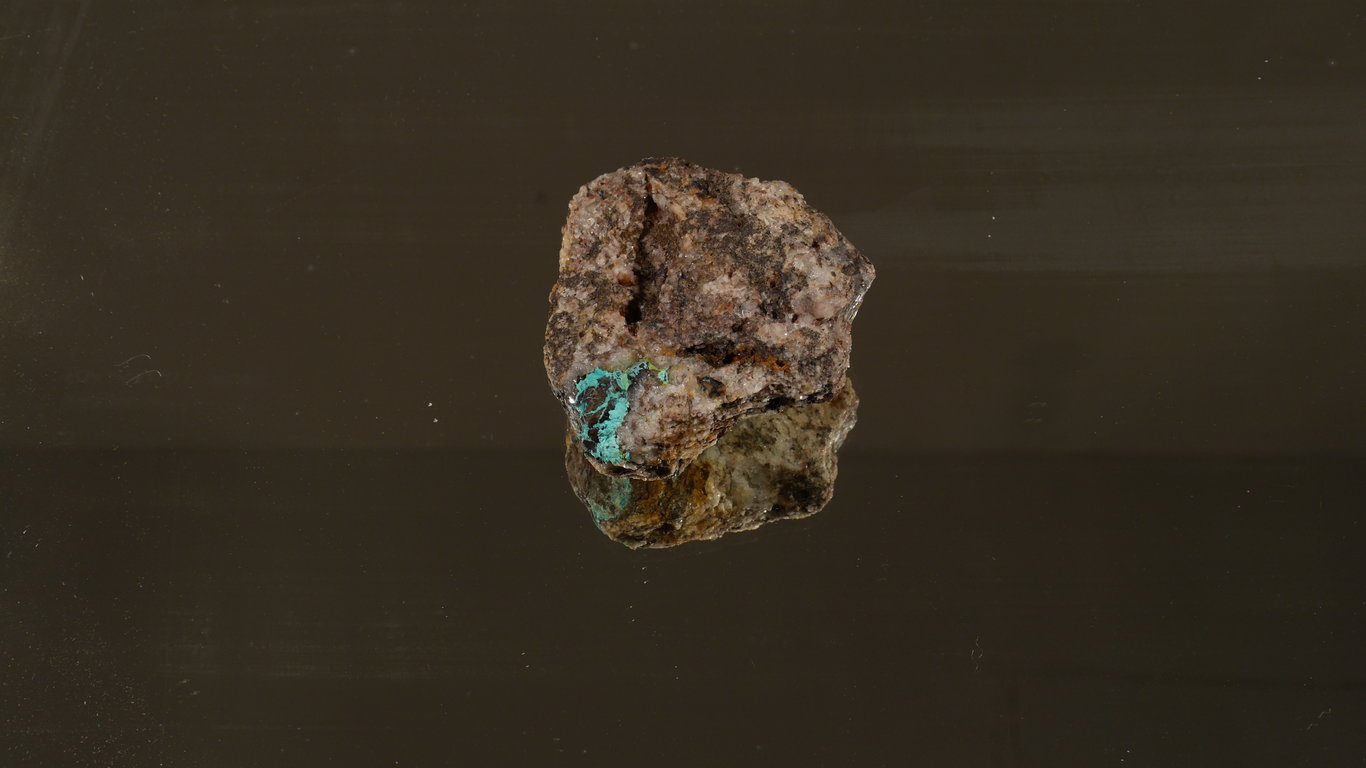

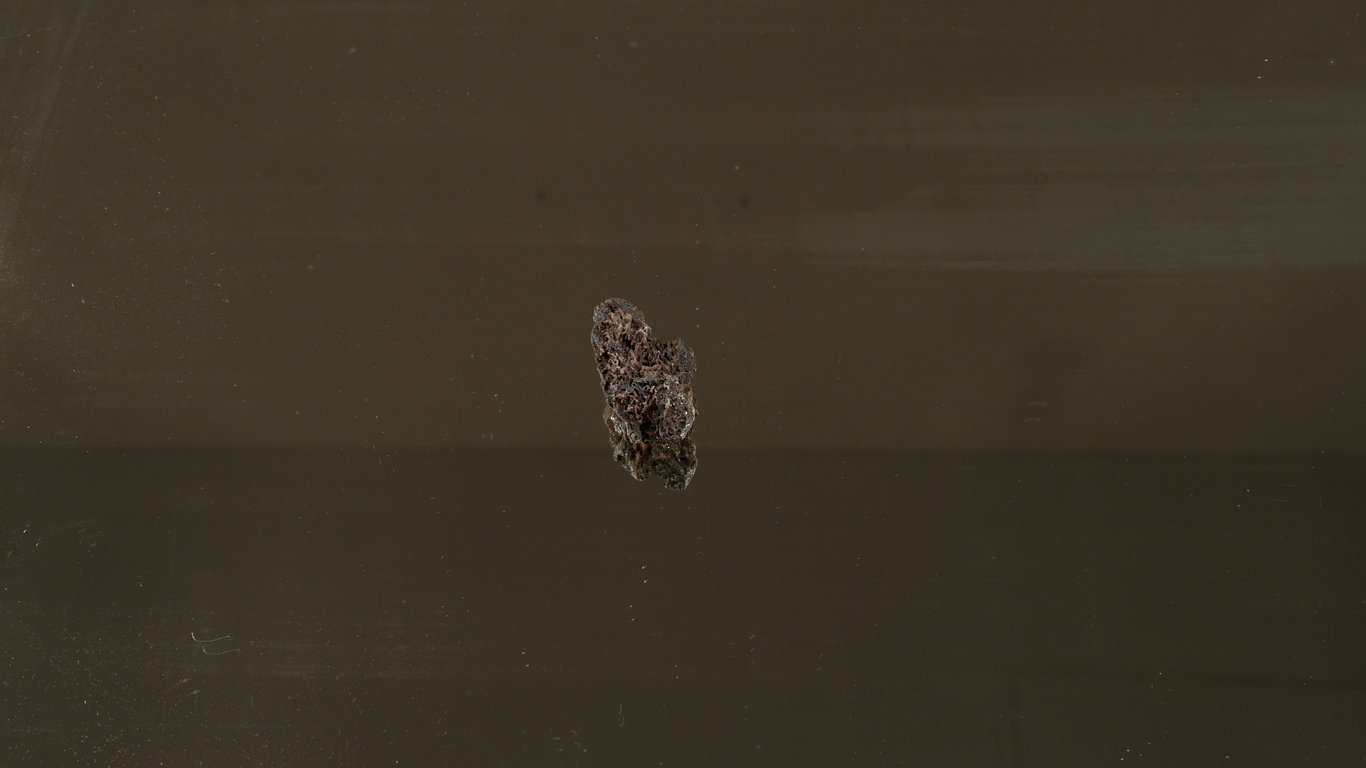

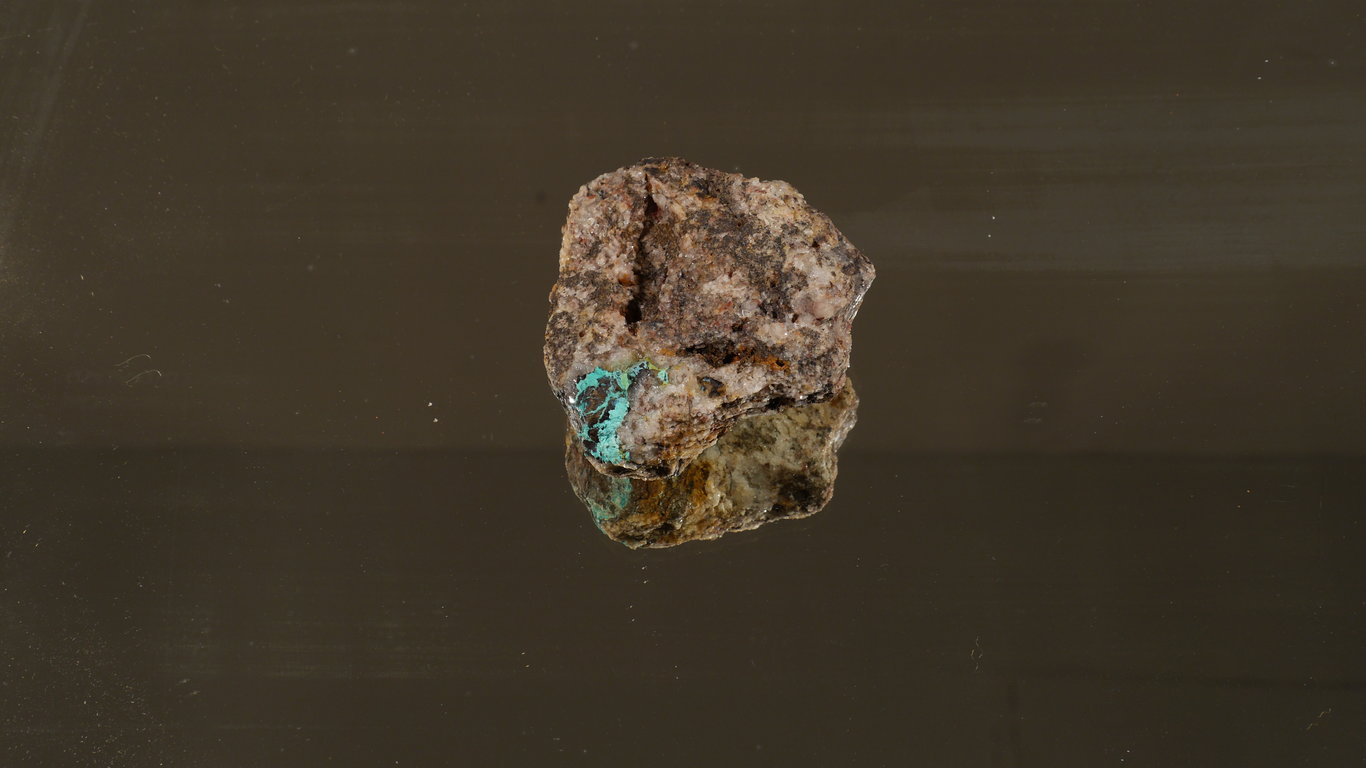

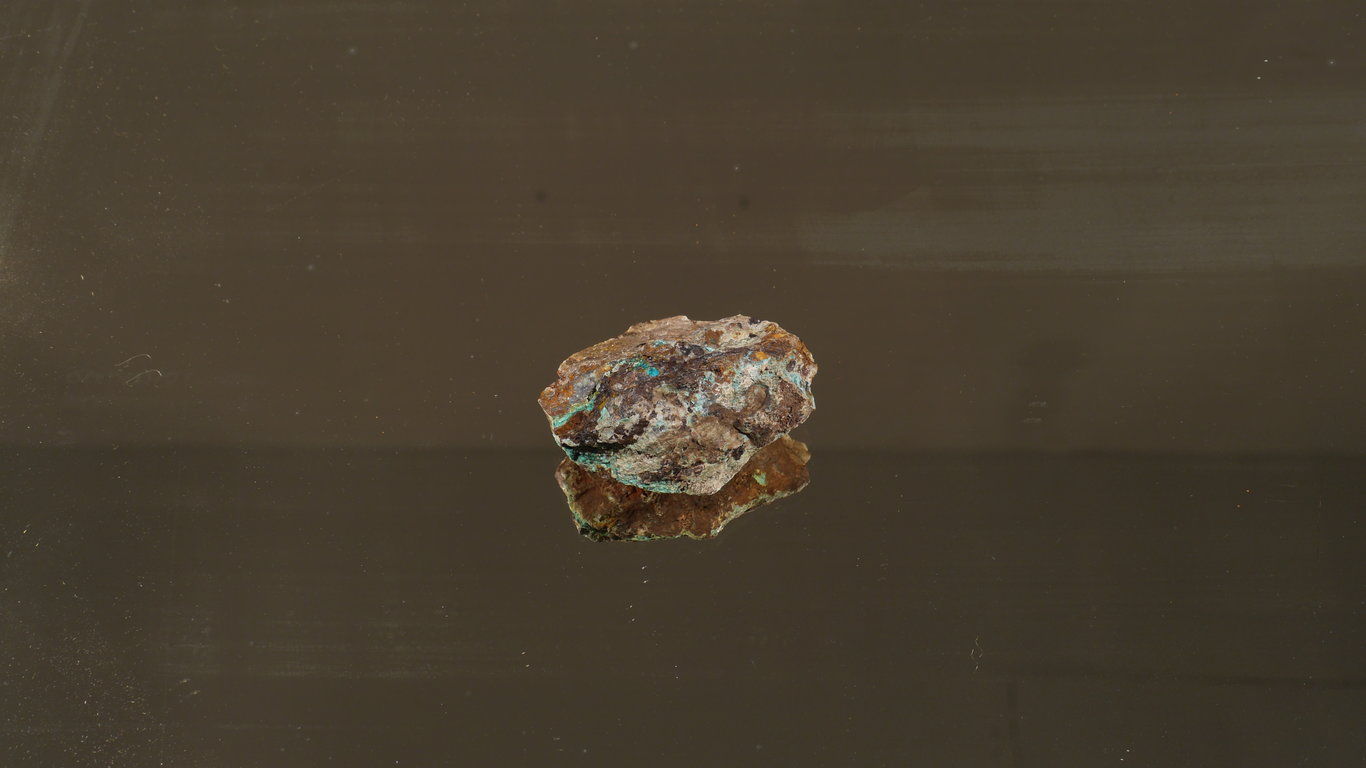

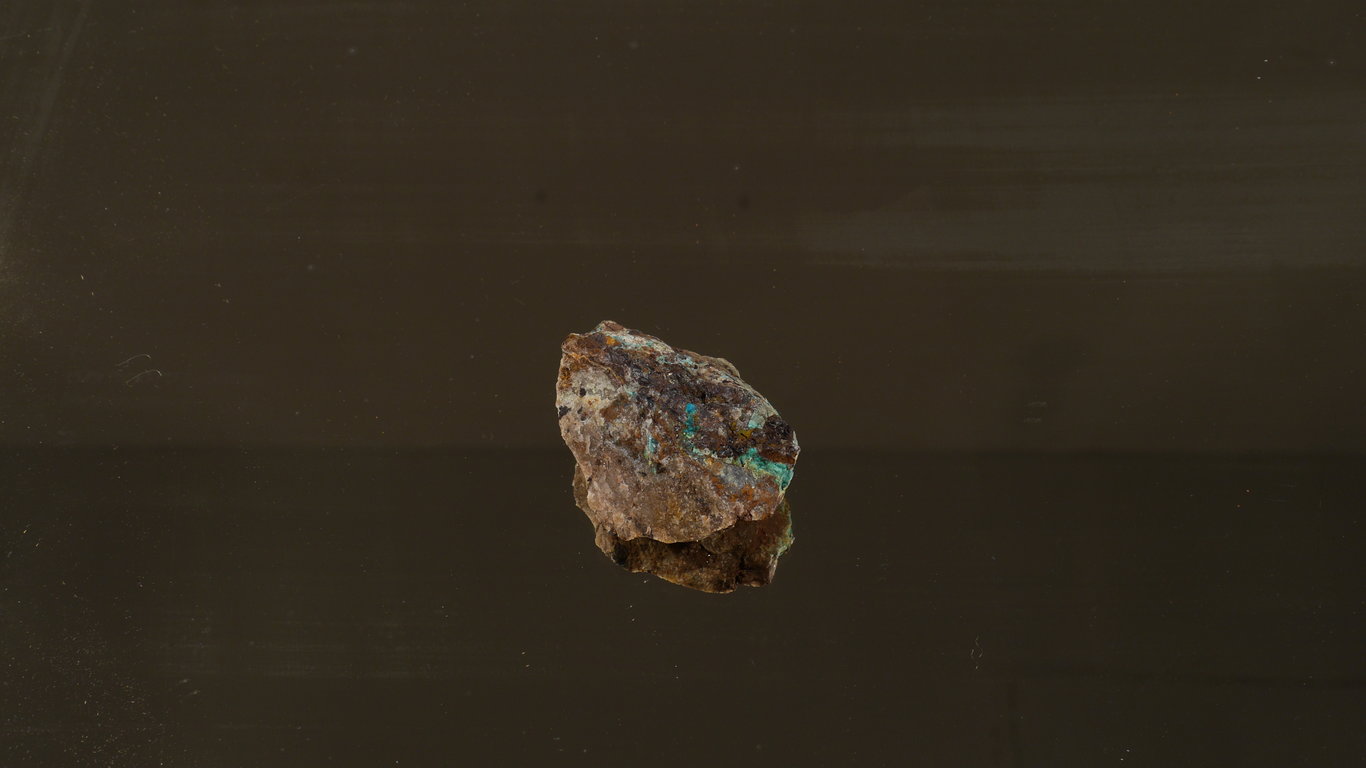

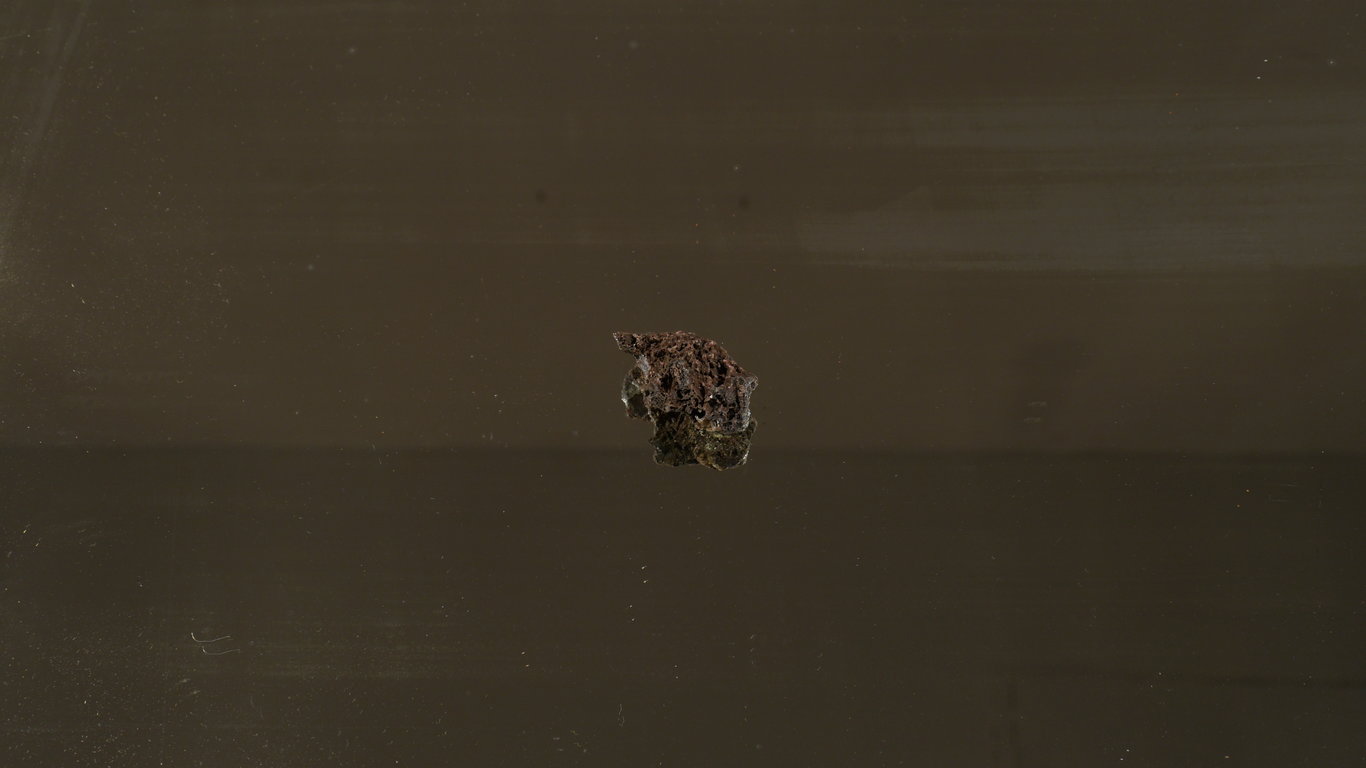

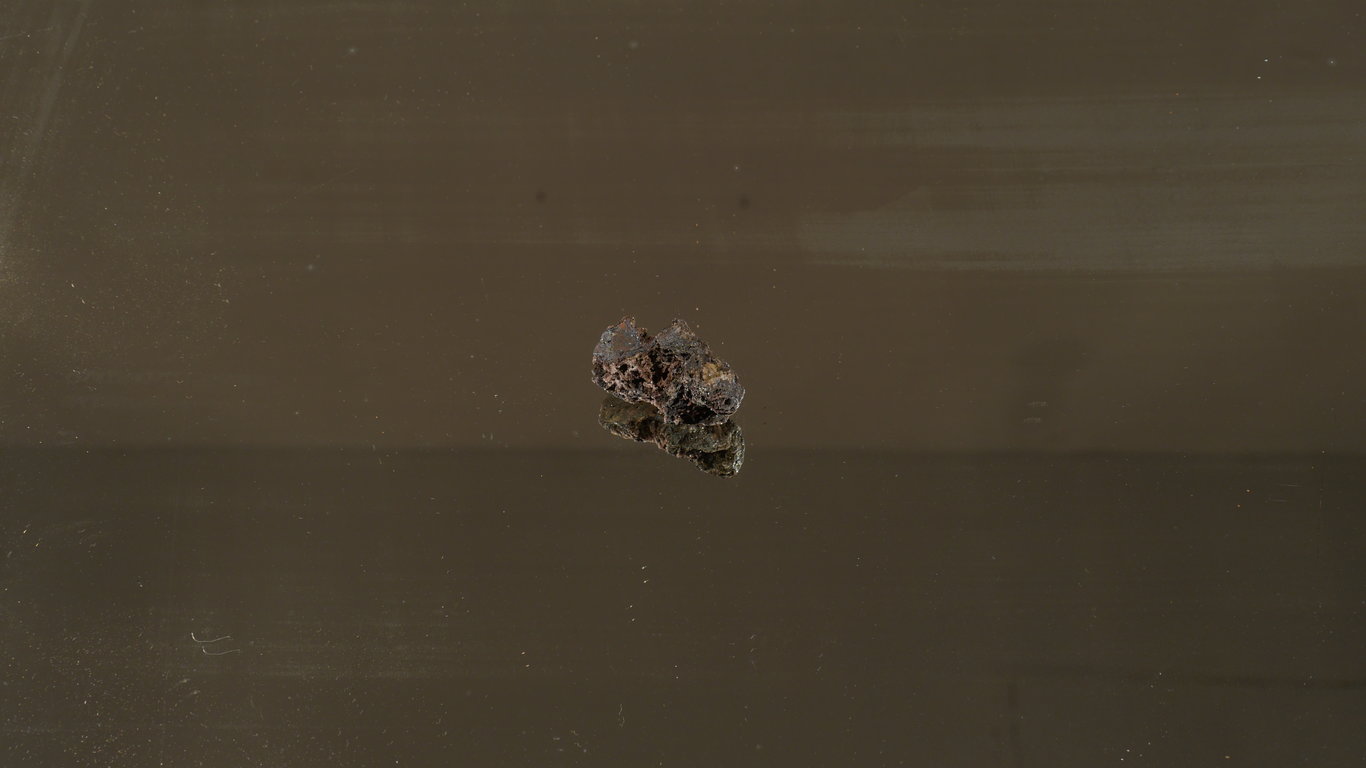

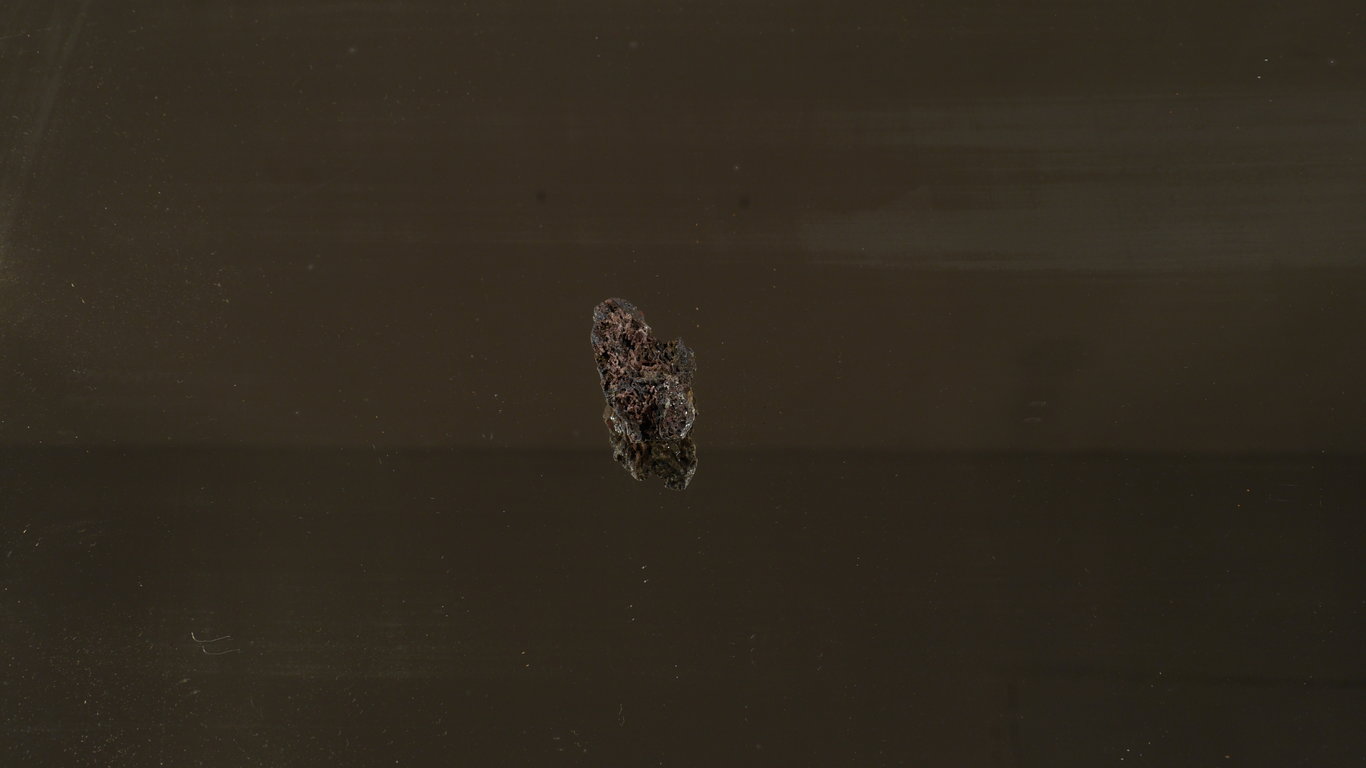

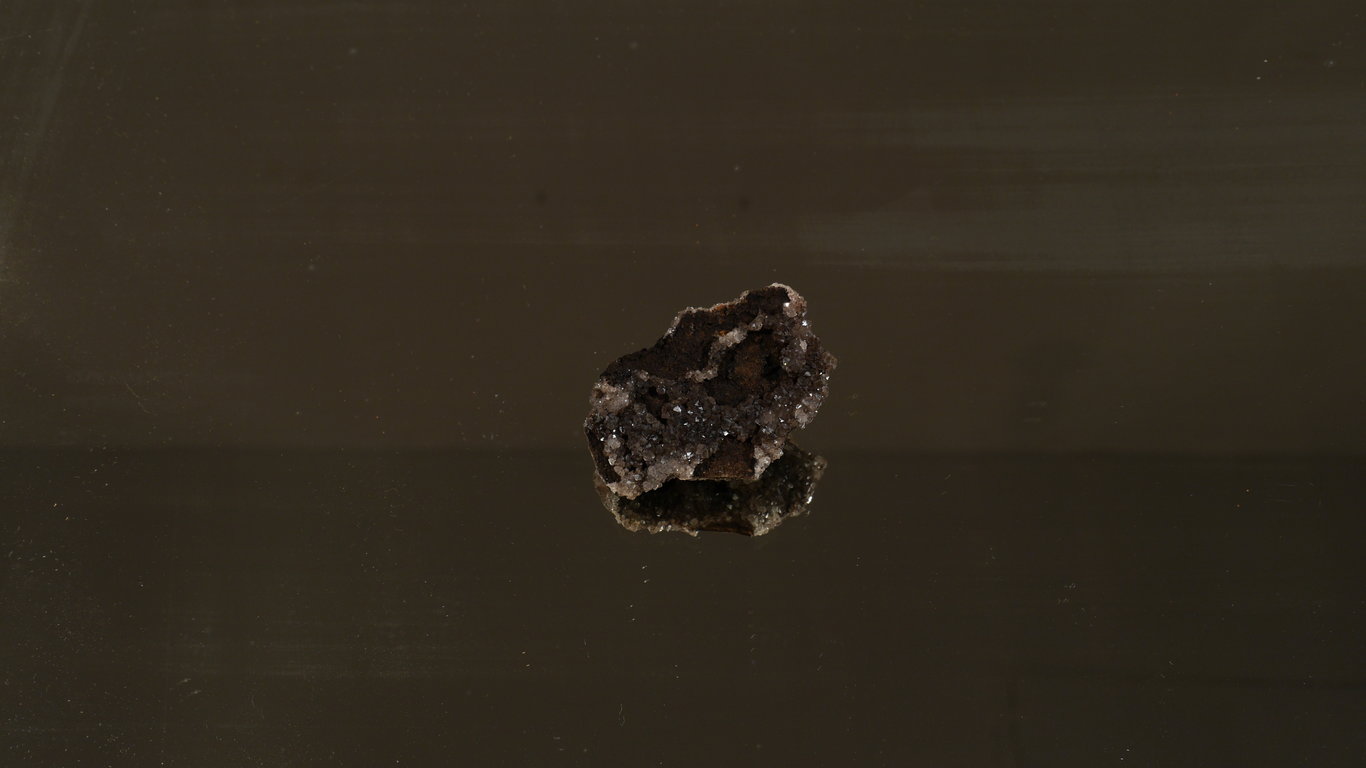

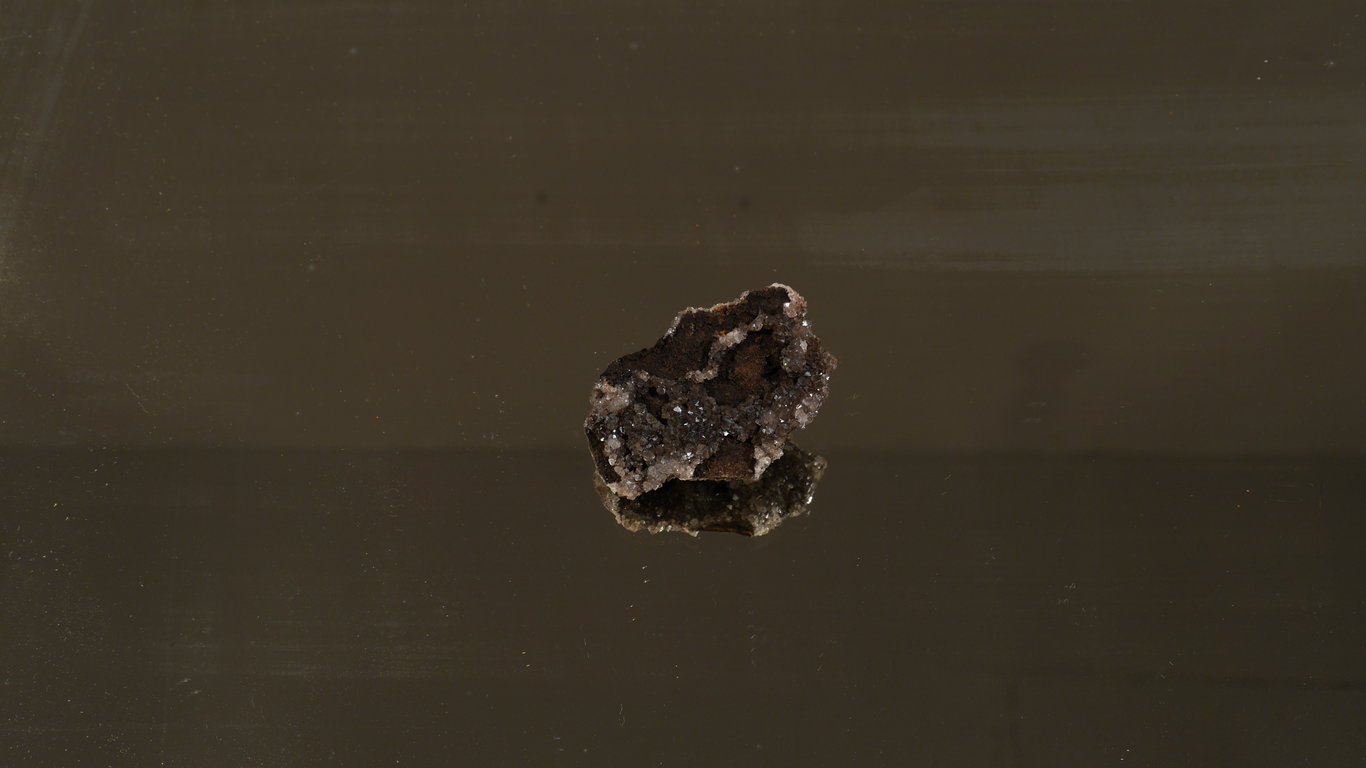

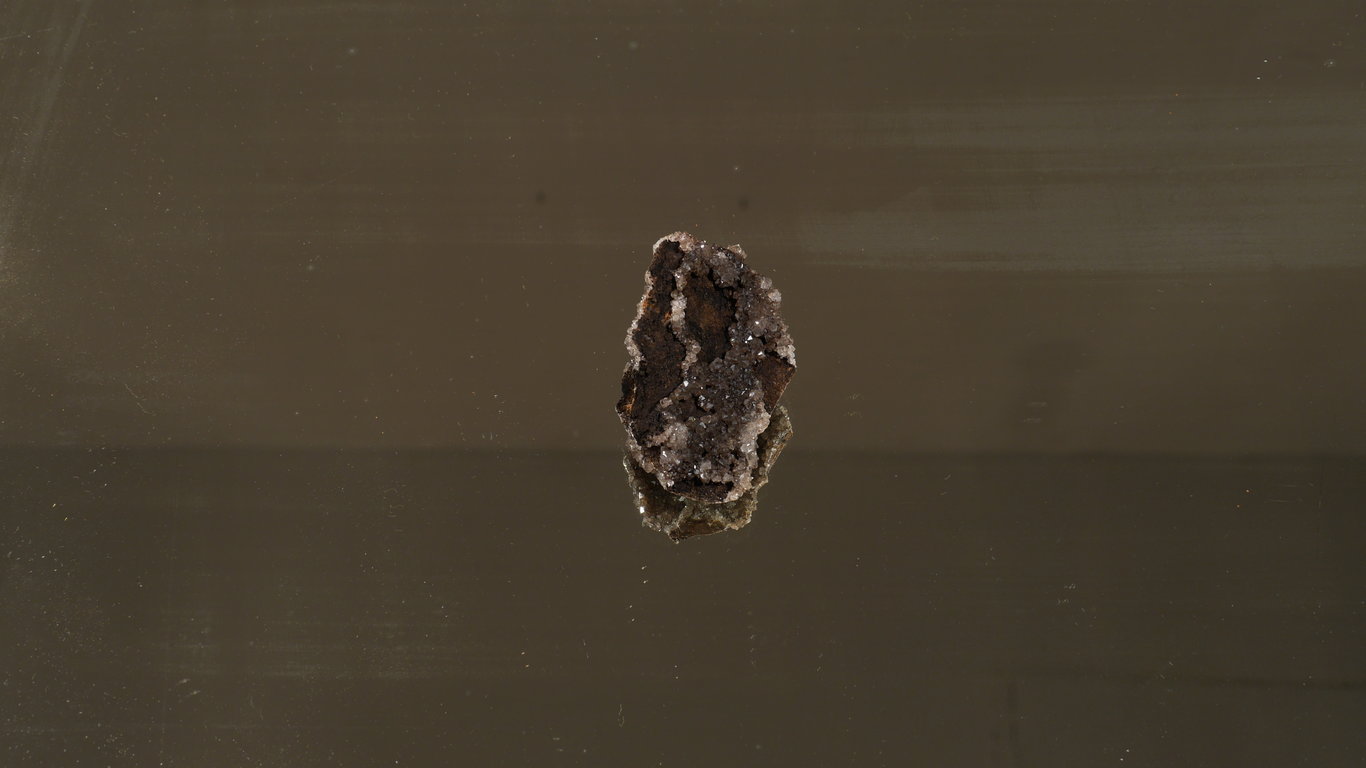

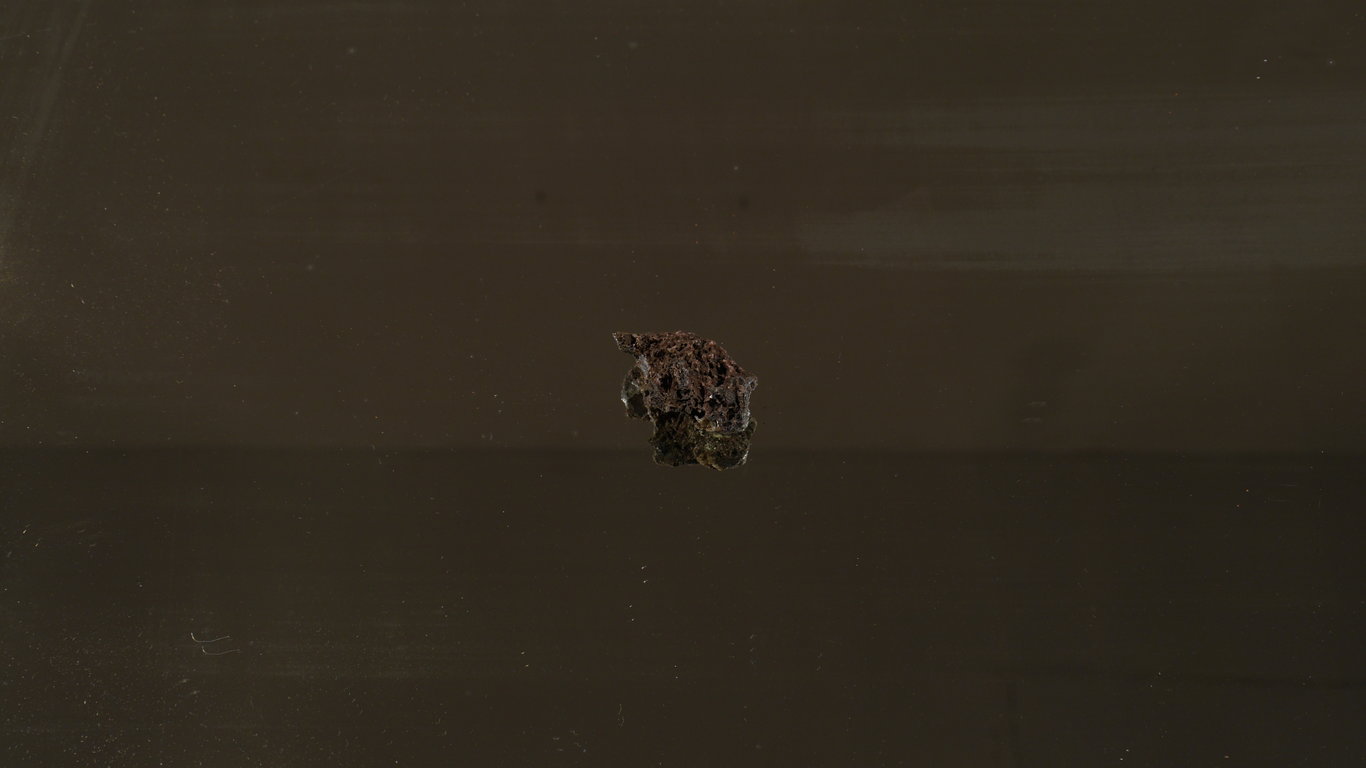

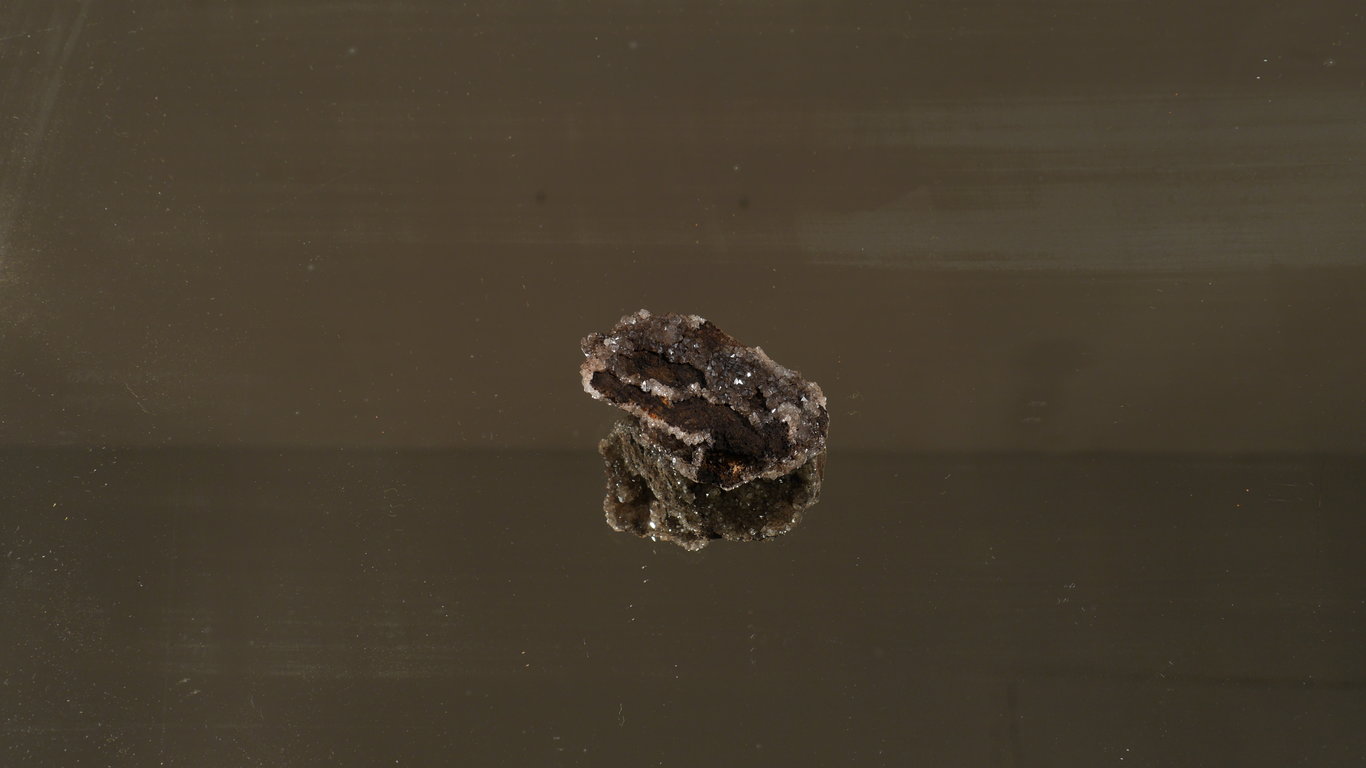

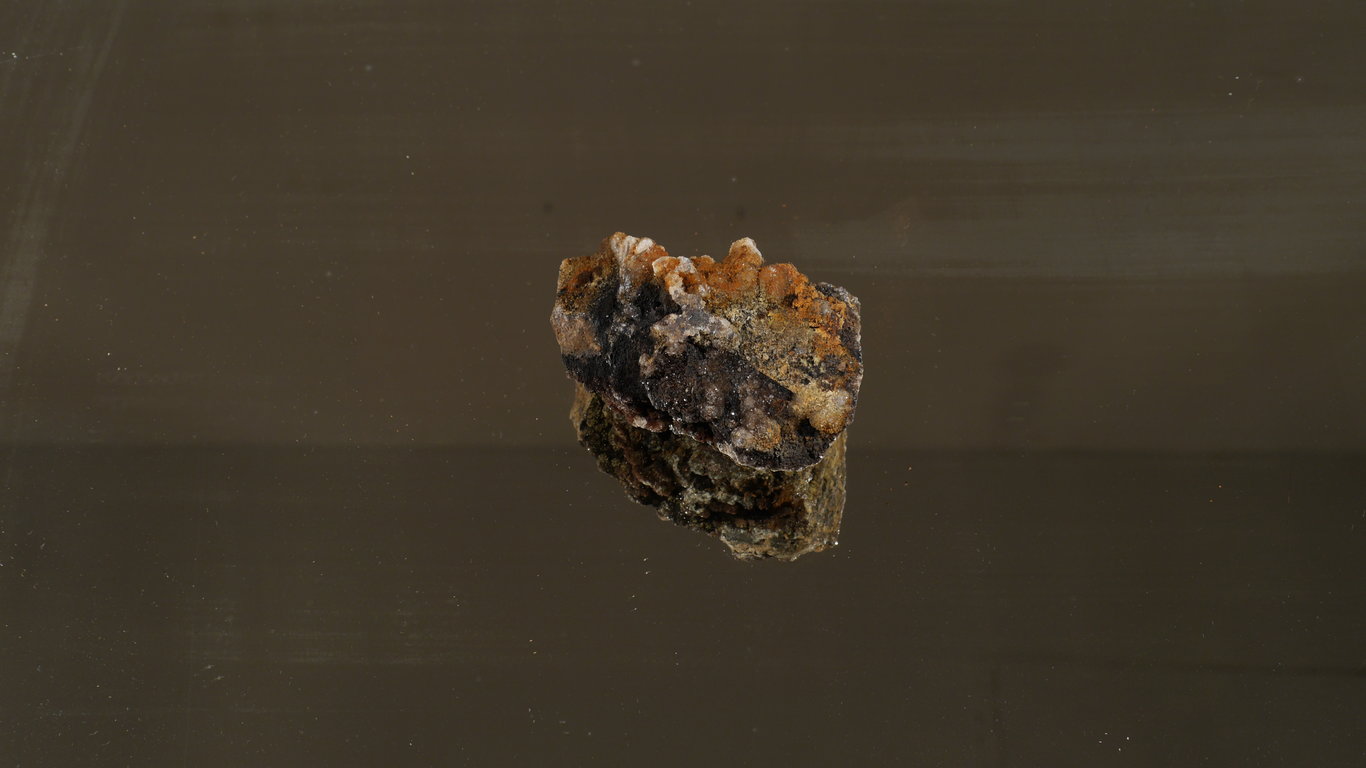

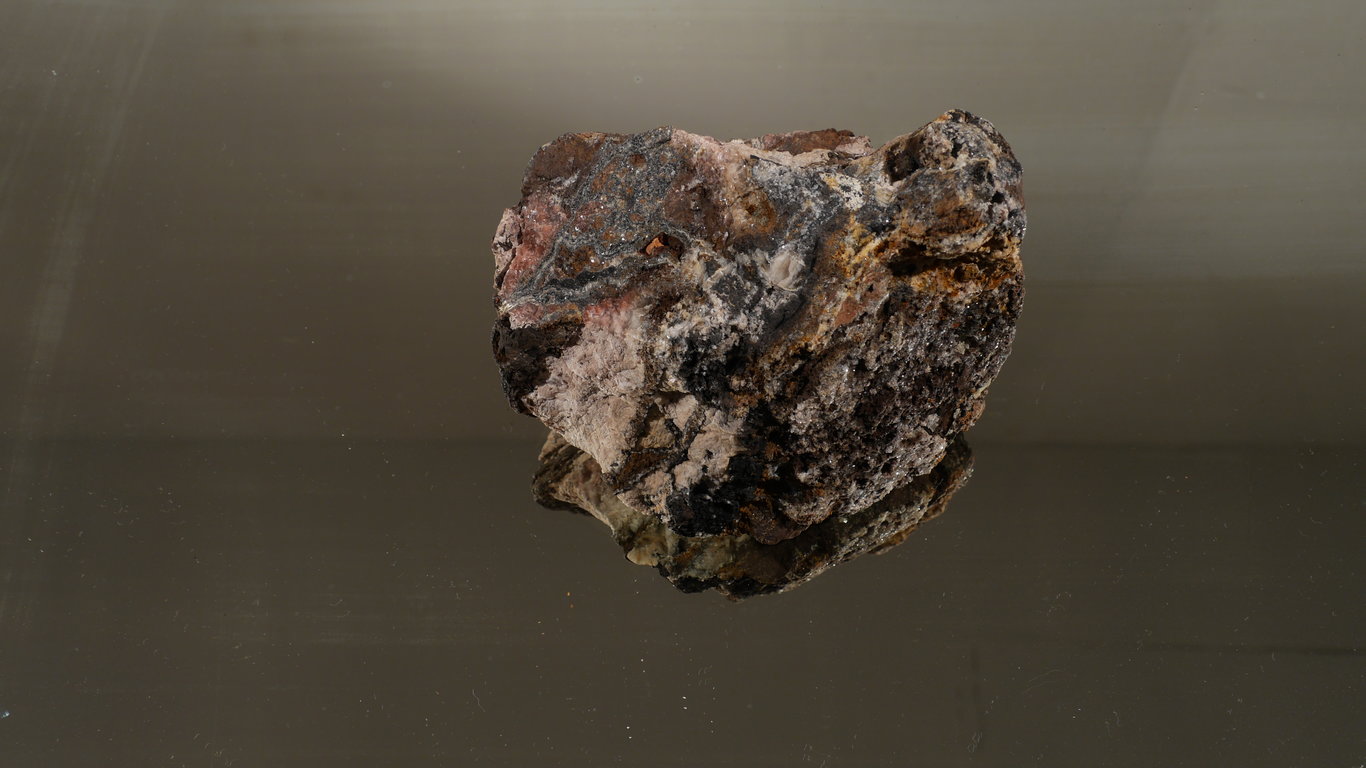

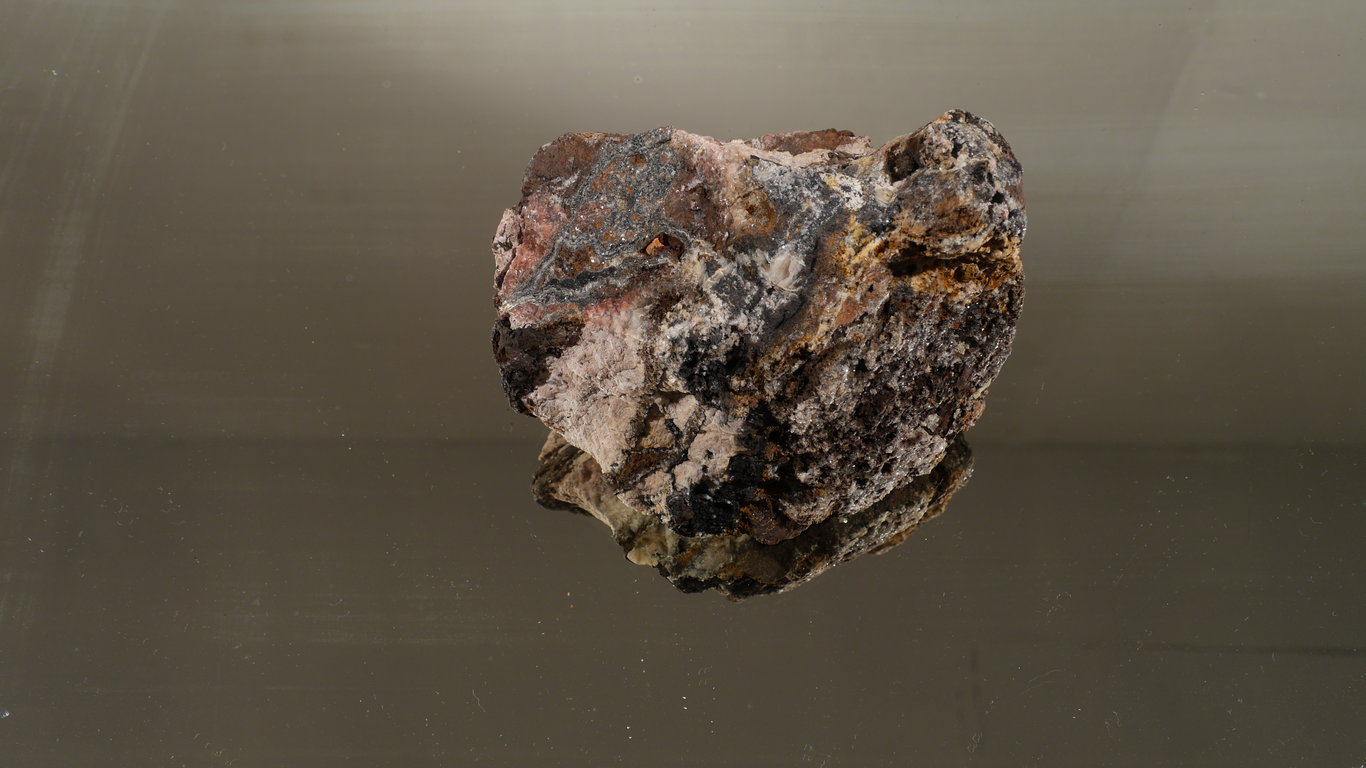

Cosmic dust, 2015

A series of photographs of rocks.

In November 2014 the European Space Agency's Rosetta Orbiter launched it's landing vehicle, Philae, to touch down on the comet known as 67p. Around this time I had been collecting mineral samples from the spoil heaps of the lead mines that surround my home. I was fascinated by their paradoxically unearthly beauty. It was a similar response that I had of the images being beamed back to the Rosetta Mission Control, in Darmstadt, from outer space.

There was something compelling about that relationship between these small samples of rock from deep within the bowels of our planet, which had never been destined to see the light of the Sun and reflect it back into our eyes, and these images of this huge, distended rock orbiting the Sun, whose countenance we were never intended to contemplate.